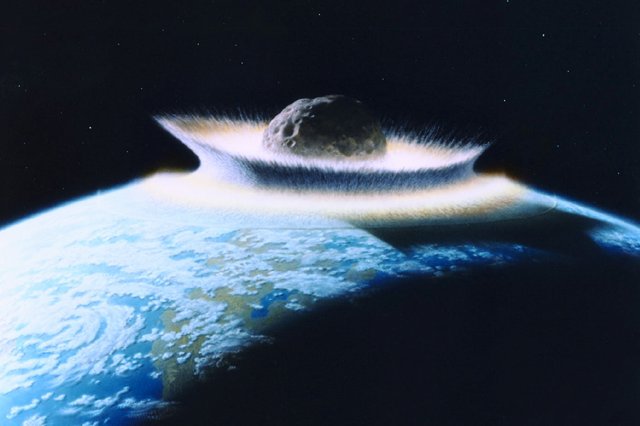

Had the asteroid that struck the Yucatan Peninsula some 66 million years ago hit somewhere else, dinosaurs might have survived, new research suggests. Photo by rw/D. Davis/NASA/UPI |

License Photo

Nov. 9 (UPI) -- When an asteroid came barreling into Earth some 66 million years ago, it wasn't necessarily a guarantee that life on planet Earth would be drastically altered -- that 75 percent of all plant and animal species, including the dinosaurs, would disappear.

According to a new study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports, there was just a 13 percent chance such a collision would prove so catastrophic.

Most scientists agree that the Cretaceous-Paleogene, or K-Pg, extinction event, was triggered by the impact of a giant space rock some 66 million years ago. Now, a pair of scientists argue the main driver of extinction was the vast amount of soot expelled into the atmosphere by the impact.

Had the rock hit elsewhere, the explosion may have emitted less soot, and the dinosaurs might have survived.

Only 13 percent of the planet hosted sufficient amounts of hydrocarbons to yield catastrophic levels of soot. That 13 percent included the Yucatan Peninsula, where the asteroid hit. The exploded soot clogged the skies, triggering global cooling and drought.

"They were unlucky," said Kunio Kaiho, a professor at Japan's Tohoku University.

Though most agree on the significance of the primary actor, the asteroid, not everyone agrees on the domino effect of geologic and ecological mechanisms that ultimately snuffed out the dinosaurs.

Some have argued the impact triggered a series of firestorms and volcanic activity, both of which could have contributed large amounts of soot. Other scientists have argued the impact released large amounts of gas, not dust, into the atmosphere. Blown high into the upper layers of the atmosphere, large amounts of CO2 and sulfur would have quickly cooled the planet.

"The 13 percent number they're quoting has a lot of assumptions based around it," Sean Gulick, a geophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin, told the Washington Post.

But Kaiho and his research partner, Naga Oshima, an atmospheric chemist at Japan's Meteorological Research Institute, claim analysis of ancient soot deposits show the hydrocarbons burned at extremely high temperature -- temperatures that could have only be generated by a massive collision, not by firestorms or magma.

No matter the odds, humans can be glad the asteroid struck where it did. With dinosaurs gone, mammals began to explore daylight hours, diversify and flourish.