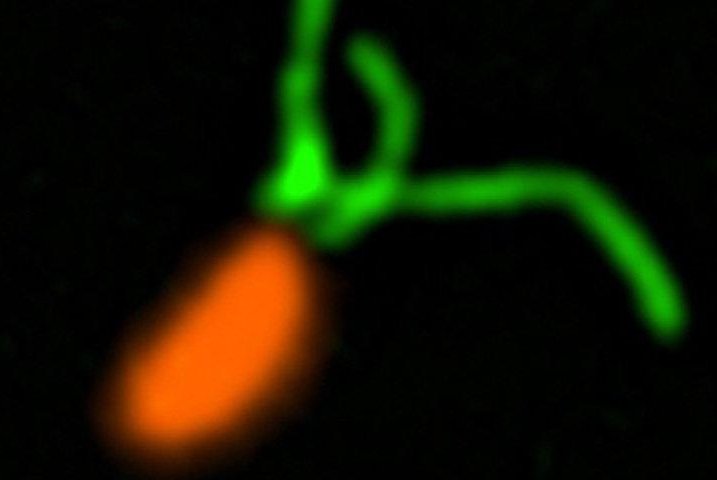

Fluorescent molecules helped scientists study the way cells use tiny appendages called pili to feel for and attach to surfaces to form biofilms. Photo by Courtney Ellison/Indiana University

Oct. 26 (UPI) -- How do bacteria sense and grab hold of surfaces, allowing biofilms to fester in hospitals and clog up sewer pipes? A new study detailing microganisms' "sense of touch" has offered some answers.

Scientists first observed a bacterium cell's feelers, or pili, hair-like appendages that sense the cell's surroundings, using targeted fluorescent dye delivered by tiny maleimide molecules. The dyes allowed researchers to watch the movement of pili under a high-powered microscope.

Researchers were able to make the pili appear larger and fluoresce by substituting the chain up amino acids that normally make up the cell's appendages with an amino acid called a cysteine. The dyes bind easily with cysteine, enhancing the appendages visibility under the microscope.

"It's like switching on a light in a dark room," Courtney Ellison, a doctoral student at Indiana University, said in a news release. "Pili are composed of thousands of protein subunits called pilins, with each protein in the chain composed of amino acids arranged like a tangled mess of burnt-out Christmas lights. Swapping out a single light can illuminate the whole string."

To better understand how bacteria grab onto surfaces and create a biofilm, scientists tricked cells into thinking they were sensing a surface. They did so by using a large maleimide molecule to block the movement of the cell's pili.

Pili can extend and retract through the cell wall to "feel" around for nearby objects. The maleimide molecule effectively blocked the pili's ability to extend and move, tricking the cell into thinking it had bumped up against a surface.

"It's like trying to pull a rope with a knot in the middle through a hole -- the maleimide molecule can't pass through the hole the cell uses to extend and retract the pili," Ellison said.

The experiment -- detailed in a new paper published this week in the journal Science -- confirmed that a cell becomes aware of a surface when the pili's movement is restricted.

"These results told us the bacteria sense the surface like how a fisherman knows their line is stuck under water," said Yves Brun, professor of biology at IU. "It's only when they reel in the line that they sense a tension, which tells them their line is caught. The bacteria's pili are their fishing lines."

Biofilms can thwart valuable infrastructure and cause deadly infections, but researchers hope their new research will help scientists develop new ways to thwart their formation and growth.

"The more we understand about the mechanics of pili in biofilm formation and virulence, the more we can manipulate the process to prevent harm to people and property," Brun said.