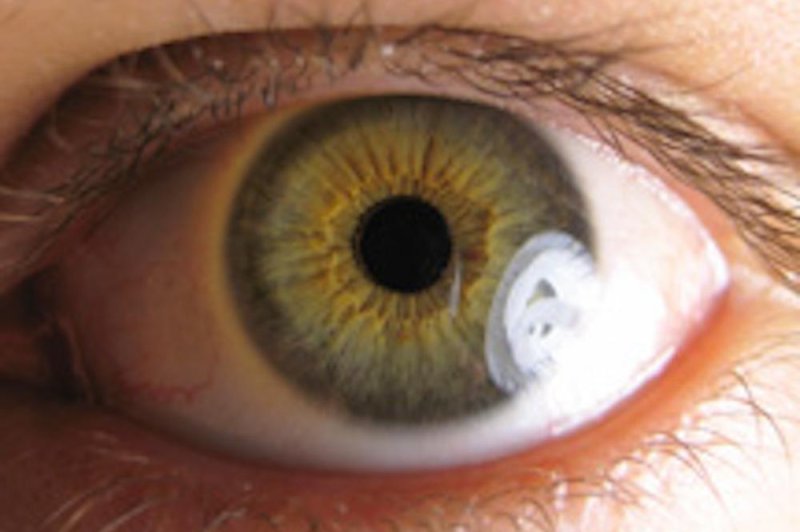

New research suggests pupil dilation operates independently of the brain in some animals. Photo by John Hopkins University

June 19 (UPI) -- New analysis suggests the iris in the eye of a mouse doesn't need the brain's help to sense light and direct the pupils to dilate or contract in response.

Neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine severed the neural connection between brain and eyes in several mice specimens and then observed the behavior of the iris as the mice were moved from a dark room to a lit room. Despite the disconnection, the mice's pupils shrank as they transitioned into the light.

The findings -- published in the journal Cell Biology -- prove the pupillary light reflex works independently of the brain.

"The traditional view of this reflex is that light triggers nerve signals traveling from the eye's retina to the brain, thereby activating returning nerve signals, relayed by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, that make the sphincter muscle contract and constrict the pupil," King-Wai Yau, a neuroscientist at John Hopkins, said in a news release.

Their latest research confirms previous studies, which showed the pupil sphincter muscle in mice, rabbits, cats and dogs functions without help from neural signals. The sphincter naturally reacts to light and releases melanopsin, a light-sensitive pigment.

In response to similar earlier findings, some researchers suggested the sphincter featured light-sensitive nerve fibers embedded directly in the muscle tissue, allowing the reflex to indirectly tap into neural circuitry and borrow the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

But when researchers blocked acetylcholine in the most recent tests, mice pupils continued to contract without neural circuitry of any kind.

"The isolated iris sphincter muscle still contracted in response to light, adding confidence to the notion that the muscle is itself light-sensitive because it contains melanopsin," Yau said. "We thus have convincingly proven that the sphincter muscle is intrinsically light-sensitive, a very unusual property for muscle."

The research suggests this local function developed in primitive animals before the advanced evolution of the brain. Over time, the brain became involved in this reflex in most animals.

"By the time mammals appeared, the local reflex was progressively less important, becoming extinct altogether in subprimates that are active during the day and in primates," Yau said. "It's the local light reflex's absence in human beings that allows doctors to quickly evaluate whether a comatose patient is brain-dead by checking his or her pupillary light reflex."