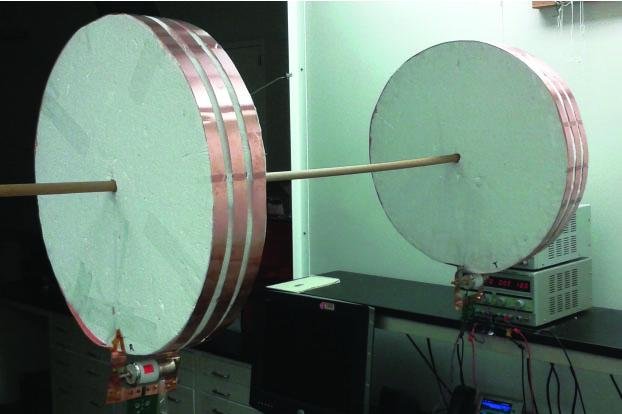

Researchers at Stanford were able to wirelessly transmit electricity between two electromagnetic coils. Photo by Sid Assawaworrarit/Stanford University

June 14 (UPI) -- Stanford scientists have made a breakthrough in the quest to wirelessly charge a moving electric vehicle.

In 2007, MIT researchers wirelessly charged a stationary object a few feet away. In recent experiments, scientists were able to wirelessly transmit electricity to a moving LED lightbulb using a similar setup.

If researchers can find a way to charge electric vehicles while on the go, it would remove the cars' biggest drawbacks -- their limited range and lengthy charging times.

"In theory, one could drive for an unlimited amount of time without having to stop to recharge," lead researcher Shanhui Fan, a professor of electrical engineering at Stanford, said in a news release. "The hope is that you'll be able to charge your electric car while you're driving down the highway. A coil in the bottom of the vehicle could receive electricity from a series of coils connected to an electric current embedded in the road."

Wireless charging relies on a electromagnetic phenomenon known as magnetic resonance coupling. Electricity rotating around a tire can form an oscillating magnetic field. This push and pull can excite electrons in a nearby coil of wires, triggering a flow of electricity.

But in order to keep a continuous flow of electricity, the sets of coils must be manually tuned to maintain the resonant frequency as they move.

Stanford scientists worked around the problem by swapping out the transmitter's radio-frequency source and installing a voltage amplifier and feedback resistor. The duo can automatically calculate the proper frequency as the distance between the coils changes.

Researchers described their breakthrough in the journal Nature.

"Adding the amplifier allows power to be very efficiently transferred across most of the three-foot range and despite the changing orientation of the receiving coil," said lead study author Sid Assawaworrarit, a Stanford grad student. "This eliminates the need for automatic and continuous tuning of any aspect of the circuits."

The team of scientists used a relatively inefficient off-the-shelf amplifier. A custom amp could boost the transmitters efficiency. And research suggests further tweaks could boost the amount of electricity the technology can transmit.

"We can rethink how to deliver electricity not only to our cars, but to smaller devices on or in our bodies," Fan said. "For anything that could benefit from dynamic, wireless charging, this is potentially very important."