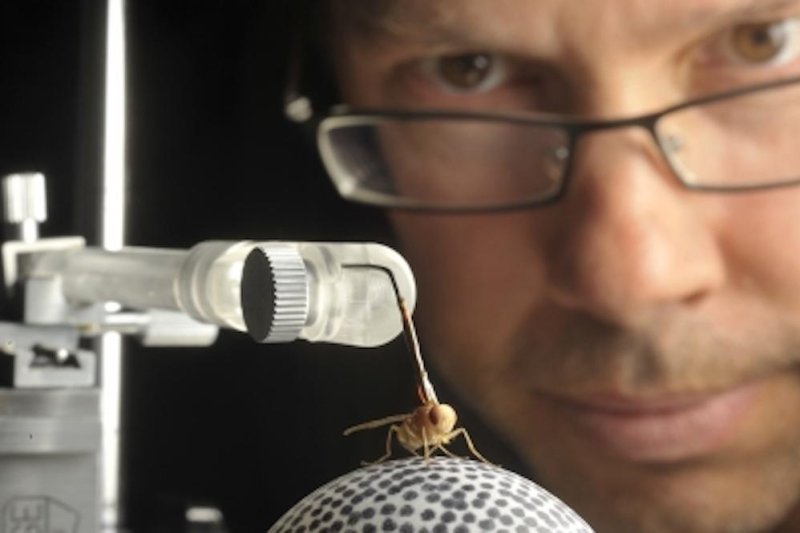

Researcher Andrew Mason is seen studying the auditory abilities of a parasitic fly. Photo by Ken Jones/University of Toronto

May 15 (UPI) -- Ormia ochracea, a small, yellow, nocturnal fly native to Mexico and the southern United States has the most powerful directional hearing in the animal kingdom.

Scientists hope the fly's hearing mechanism can inspire the next generation of auditory sensors, but new research suggests the fly's hearing mechanism has limitations.

"These flies have highly specialized ears that provide the most acute directional hearing of any animal," Andrew Mason, a professor of biology at the University of Toronto, Scarborough, said in a news release. "The mechanism that makes their hearing so exceptional has even led to a range of bio-inspired technology, like the mini directional microphones used in hearing aids."

Unlike most animal ears, the fly's are connected. A pair of eardrums are connected by a bendable joint. When one is stimulated, the vibrations reverberate across to the other. The time delay helps the fly pinpoint the direction of the sound.

The remarkable ability helps the fly locate the songs of male crickets. Ormia ochracea is parasitic. The females burrow their eggs in the cricket. The fly's larvae eat the cricket alive as they develop.

Unfortunately, for auditory engineers, the mechanism that makes the hearing of Ormia ochracea so remarkable isn't easily translated to new technology.

One of the main challenges for engineers designing improved hearing aids is the "cocktail-party-problem." How can a hearing aid be designed to isolated target sound in a noisy environment. For humans, the brain and auditory system work together to hone in on localized sounds -- the ability is called "spatial release from masking," or SRM.

The ears Ormia ochracea can't perform SRM. Lab tests showed the fly is easily pulled away from its target by distracting sounds.

"A distracting noise that is more to one side will cause an auditory illusion by obscuring the signal in that ear," said Mason. "It essentially ends up fooling the fly into perceiving that the signal is coming from one place, so it ends up pushing it away from the actual cricket sound."

The new research, detailed in the journal eLife, highlights a potential limitation of mechanically-coupled hearing devices.

"These flies are very accurate for one thing, which is detecting cricket sounds, but that comes at a cost since they've evolved to focus on this very restrictive set of information," Mason said.