May 3 (UPI) -- The western spotted skunk, the 2-pound smelly creature, evolved more than a million years ago because of climate, according to new research.

Adam Ferguson, the collections manager of mammals at the Field Museum in Chicago, is the lead author of a new study, published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, that examined how the spotted skunk can live in a variety of climates across the western United States and Mexico.

"By analyzing western spotted skunk DNA, we learned that Ice Age climate change played a crucial role in their evolution," Ferguson said in a press release. "Over the past million years, changing climates isolated groups of spotted skunks in regions with suitable abiotic conditions, giving rise to genetic sub-divisions that we still see today."

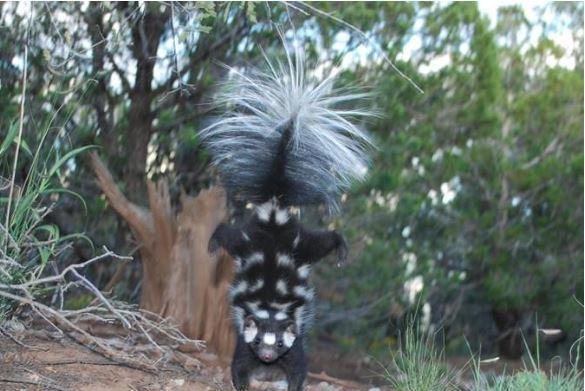

The skunks' coats are almost maze-like with black and white swirls. They ward off predators by spraying with a hand-stand, with hind legs and fluffy tail in the air.

"Skunks are a really interesting family of North American carnivores -- they're well-known, but not well-studied," he said. "And studying them comes with a cost -- they stink, even their tissues stink, and you run the risk of getting sprayed. But they're important to their ecosystems -- for example, they eat insects and rodents that damage our crops."

The skunks, which are 18 inches long, thrive in a variety of climates.

"One of the reason we're interested in this species is it exists from the Sonoran desert, to the temperate rainforest of British Columbia to Wyoming, so the habitats and the climates in which they live are quite diverse," Adam Ferguson said to Newsweek.

Western spotted skunks have been around for a million years, since the Pleistocene Ice Age.

"During the Ice Age, western North America was mostly covered by glaciers, and there were patches of suitable climates for the skunks separated by patches of unsuitable climates," Ferguson said. "These regions are called climate refugia. When we analyzed the DNA of spotted skunks living today, we found three groups that correspond to three different climate refugia.

"That means that for spotted skunk evolution, climate change appears to have been a more important factor than geographical barriers."

In the study, scientists used DNA samples from 97 skunks from a variety of regions and climates in southwest United States.

"Small carnivores like skunks haven't been well-studied when it comes to historical climate change," Ferguson said. "We know how small mammals like rodents respond to changing climates, and we know how bigger carnivores like wolves respond, but this study helps bridge the gap between them."

Ferguson was born in Houston in 1980.

"As a kid, like most individuals who enter this field, I spent my time searching the ditches, bayous, and back woods for water moccasins, snapping turtles, and an array of anurans," he said on his website. "I used to trap raccoons, opossums, and feral cats in my back yard with Hav-A-Hart live traps just to see them up close [minus the cats of course]."

He has a doctorate in philosophy at Texas Tech and science master's degrees from Texas State and Angelo State.

"Although my research interests are diverse, they typically are geared towards understanding the ecology, geographic distribution, and evolutionary history of this group of incredible animals," said Ferguson on his website.

Ferguson's co-authors are affiliated with Angelo State University, the National Museum of Natural History, the National Zoological Park, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the University of New Mexico.