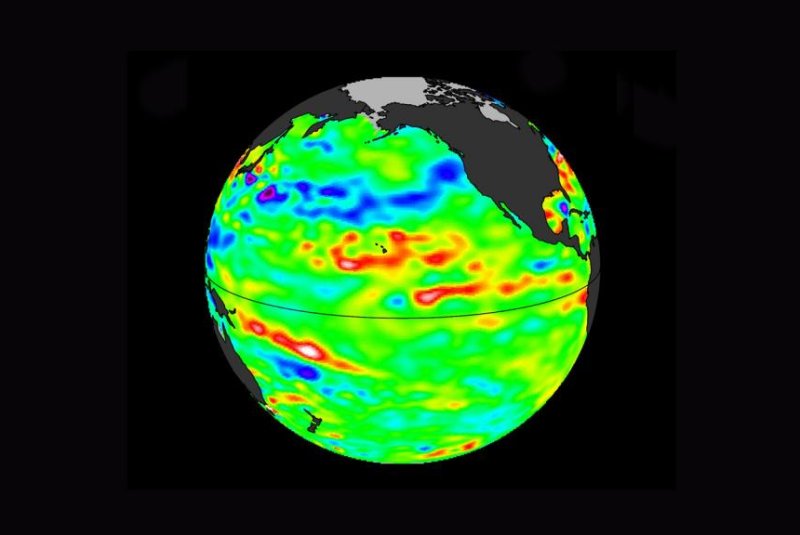

Sea level data show a warm band surrounding Hawaii, heat leftover from the last El Niño, which researchers say could fuel a new one. Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech

March 15 (UPI) -- For climate scientists and meteorologists, predicting the emergence of El Niño and La Niña is one of their most difficult tasks. Currently, researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., are trying to do just that.

Their latest analysis of sea levels in the Pacific Ocean -- along with several climate models -- suggests a new El Niño could emerge with the help of heat left behind by the last warm water event.

Sea level maps populated by data from the Jason-3 satellite mission show a bulge of high seas surrounding Hawaii, a band of warm water leftover from the last El Niño.

The last El Niño formed in 2015 and grew to an impressive size, influencing global weather patterns. It reached full strength in January of 2016, but faded in the spring. The pattern's warming influence remained, however, and scientists believe its residual heat prevented a full-blown cooling pattern.

"Did the warm bulge suppress the trade winds in the eastern and central Pacific, muting the conditions required for a full-blown La Niña to form?" JPL climatologist Bill Patzert asked in a news release. "As all El Niño researchers know, no two El Niño or La Niña episodes are exactly the same."

The El Niño and La Niña phenomena are the warm and cool phases of what's known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, which is part of a larger ocean temperature pattern called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. The PDO alternates between warm and cool, or positive and negative phases, in irregular periods of 5 to 20 years. PDO phases strongly influence the ENSO pattern.

Patzert and his colleagues are currently modeling PDO patterns in an effort to determine whether the remnants of the last El Niño will grow into a new cross-Pacific band of weather-altering warm water.

For now, the Pacific sits idle in what Patzert calls a "La Nada" state, a neutral phase, neither exceedingly warm nor cool. But that could change, depending on if and when PDO patterns shift.

"A warmer or cooler Pacific Ocean will certainly play a big role in future El Niño and La Niña events," Patzert said. "That's important, because these events modulate drought and deluge patterns in the American West, as well as the rate of climbing global temperatures."