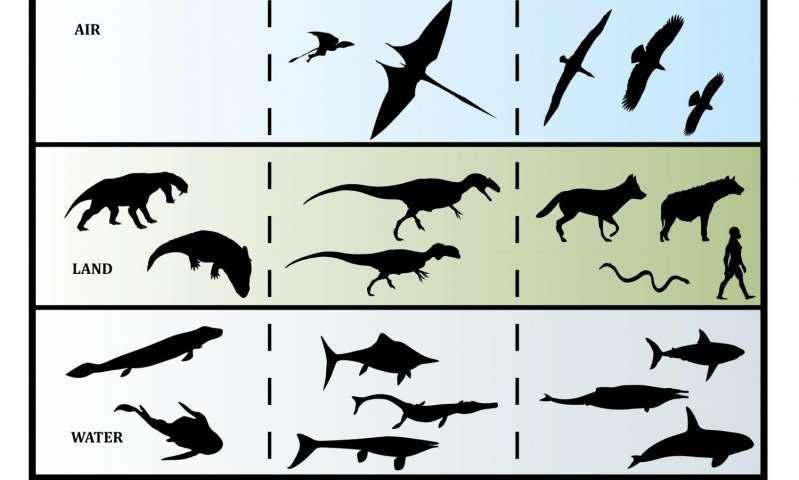

Researchers plotted their scavenging scale across time and space, detailing how species have scavenged in different settings through evolutionary history. Photo by Adam Kane et al./Ecography

Feb. 7 (UPI) -- What makes a scavenger a scavenger? What physiological features differentiate a scavenger from a predator?

New research suggests there is no obvious dichotomy separating scavengers from predators. Instead, scientists say all meat-eaters can be placed on a scavenging scale.

A scavenger, like the vulture, is capable of the occasional hunt, while lions, if desperate enough, will sometimes scavenge. Some species, however, are better suited for scavenging than others.

Generally speaking, a good scavenger must be able to move freely and cover vast areas, and they must also be able to locate -- or sense -- dead animals.

When researchers organized a variety of species on a scavenging scale, they found different scavenging skill sets are required for different environs. They also found some surprises.

Albatrosses, for example, are built and behave much like vultures. Yet, they use their scavenging skills to pluck dead squid floating on the surface of the ocean, while vultures stick to land.

One might think cheetahs -- given their similarities with hyenas and the vast amounts of carrion available on the savanna -- would be adept scavengers. But cheetahs are built exclusively for brief bursts of speed; they don't cover vast distances very efficiently. They're also easily bullied off carrion by other cats.

Researchers say their scale -- detailed in the journal Ecography -- can accommodate extinct species as well as Homo sapiens.

"What's really interesting is that we can also place long-extinct species on this scavenging scale and get a sense of whether or not they were likely capable scavengers, which helps us build a more complete picture of the past," Adam Kane, a researcher fellow at University College Cork in Ireland, said in a news release.

"For example, despite having keen senses, it would have been too metabolically costly for large meat-eating dinosaurs to search the huge areas required to find enough food from carrion alone," Kane said. "And so, Tyrannosaurus only finds itself in the middle of the scale."

Researchers suggest early humans, prone to cooperation, likely used their tool-wielding skills to regularly put carrion on the dinner table.