Residents of Anchorage, Alaska, found themselves enjoying a stretch of relatively balmy weather in December, with temperatures at times climbing above freezing. More southerly cities near the Canada-U.S. border, meanwhile, sat in the grip of a deep freeze, with some double-digit temperature drops triggering extreme cold weather alerts.

You can blame the dreaded "polar vortex," a term popularized in early 2014, when record low temperatures descended across Canada and the United States.

What's less clear is whether the polar vortex is changing because of a warming Arctic – and whether North Americans are going to have to get used to those frigid winter temperatures.

"There's a lot of things we're realizing now have never happened before," said Jennifer Francis, a research professor in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences at Rutgers University.

But to understand the possible changes, it's important to know what the polar vortex is.

First of all, it's nothing new. The polar vortex is an area of low pressure and cold air that circles over the North Pole, high up in the Earth's stratosphere. There's a second vortex above the South Pole.

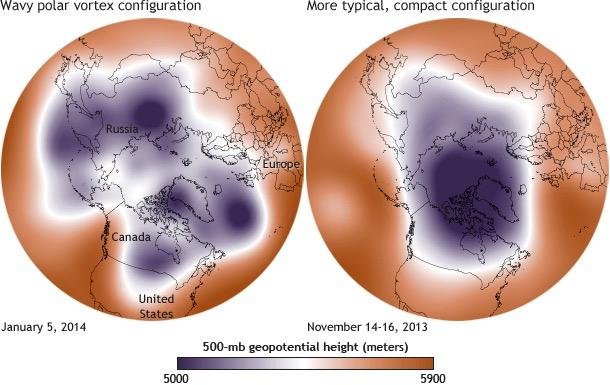

When the polar vortex is strong, it keeps cold air up in the Arctic. But when it weakens, pieces of it can migrate southward.

Down on the ground, the winter weather we experience is partly controlled by the jet stream, a current of strong wind moving west to east below the polar vortex.

Francis explained that when the polar vortex weakens, it makes the jet stream wavier – instead of moving in a straight line, it starts to swing north and south.

That can bring ridges of warm weather northward – to Alaska, for instance – while troughs of Arctic air settle over eastern North America. And once it arrives, the cold weather tends to stick around.

"When we have bigger waves in the jet stream ... they tend to be very persistent," said Francis. "We see longer-lasting cold spells and longer-lasting warm spells."

As to whether those waves are becoming more common because of climate change, scientists have yet to reach a consensus.

Francis said there's "a fair bit of evidence" that the jet stream is getting wavier as the Arctic warms, which is currently happening twice as fast as the global average.

That's because the jet stream forms the boundary between cold air to the north and warm air further south. As the Arctic warms, Francis said, the temperature difference gets smaller and the jet stream winds weaken.

"You can think of it like a river of water," she said. When a river flows down a mountainside, it stays straight and fast-moving. But when it hits the plains, it slows down and is more easily deflected from its path.

Francis said more and more scientists are convinced there's a link between a weakening polar vortex, a wavy jet stream and a warmer Arctic. But not everyone agrees.

James Overland, an oceanographer at the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said the waviness of the jet stream is "pretty much completely random."

"What quite a few of us are saying is the wavy pattern itself is all random," he said. "It's chaos on a rotating planet."

But that's not to say climate change isn't having any impact. Overland said that once the jet stream starts to move in waves, a warming Arctic can help "reinforce and prolong" the pattern.

And this year, he said, is a prime example.

Last week, the North Pole was hovering near the melting point, with Arctic temperatures nearly 30C (54F) warmer than average.

And NOAA's annual Arctic report card found that Arctic sea ice has been exceptionally slow to regrow this fall. In fact, sea ice extent from mid-October to late November was the lowest since the satellite record began in 1979.

Overland said the warm ridge extending north of Alaska is probably delaying freeze-up in the Arctic Ocean. In turn, the open water releases warm air into the atmosphere. That helps to lock in the warm weather in the Arctic and the cold weather farther south, which further prevents ice from forming – what scientists call a positive feedback loop.

"The fact that we're seeing that positive feedback between the wavy pattern and the delay of freeze-up of the ice is something new," he said. "We certainly expect to see more of this happening in the future as the ice goes away."

Still, that doesn't mean city dwellers stung by the polar vortex are going to see cold snaps every winter.

"You won't necessarily see the cold outbreaks ... unless you also have that random wavy pattern," Overland said.

But he does think cold spells will be locked in for longer when they do occur, particularly in December, at the beginning of Arctic Ocean freeze-up.

Other recent research supports the idea that the polar vortex is changing, and Arctic sea-ice melt has something to do with it.

A 2014 paper in the journal Nature Climate Change found that decreased sea ice in the early winter is linked to a weakened polar vortex and colder temperatures farther south.

Another study in the same journal, published in October 2016, found that the polar vortex has shifted toward Eurasia and away from North America over the last three decades. The researchers also linked that shift to a decline in sea ice.

Still, other scientists maintain there's no proof that climate change is having an effect. Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist with the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research, has argued that the tropics have more of an influence on global weather than the Arctic.

"These events are complicit and there is some randomness to them: We call it 'weather,'" he recently told the Washington Post.

Overland said there's a spectrum. "There's some people that say it's all random, and I'm somewhere in the middle between Jennifer [Francis] and them," he said.

But he and Francis work closely together, despite any disagreements. "We've been this way for five years, so some of the rough edges have worn off."

If Francis is right, that would spell bad news for the Arctic and for people in parts of southern Canada and the northern United States who aren't fond of frigid winter temperatures. Still, she believes there's a silver lining.

"I think the fact that the Arctic is changing so fast and so conspicuously, it's helping the public to become aware," she said.

"It's a climate change story that we can tell that helps people make the connection between their own behaviors and the extreme weather that they are experiencing themselves."

Maura Forrest is a Canadian journalist based in Whitehorse, Yukon. This article originally appeared on Arctic Deeply, and you can find the original here. For important news about Arctic geopolitics, economy, and ecology, you can sign up to the Arctic Deeply email list."

![]()