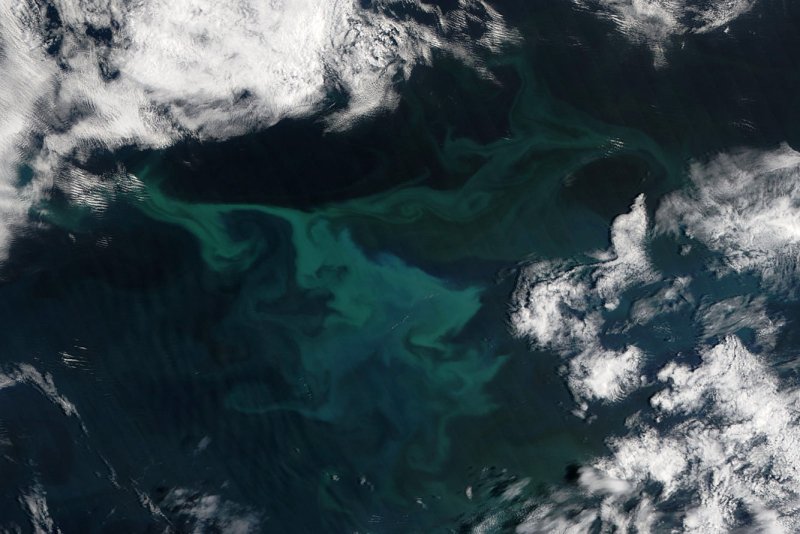

Lidar Instruments mounted on satellites help scientists image and monitor plankton blooms in the ocean. Photo by UPI/J.Schmaltz/NASA |

License Photo

CORVALLIS, Ore., Dec. 19 (UPI) -- Improved lidar technologies are helping scientists better understand the drivers of plankton boom-bust cycles. New analysis suggest the push and pull between plankton and predators is stronger than previously thought.

"It's really important for us to understand what controls these boom-bust cycles and how they might change in the future, because the dynamics of plankton communities have implications for all the other organisms throughout the web," researcher Michael Behrenfeld, an expert in marine plankton at Oregon State University, said in a news release.

The Cloud-Aerosol Lidar with Orthogonal Polarization, or CALIOP, a satellite-mounted lidar instrument, has been monitoring phytoplankton blooms for the last decade. Ten years of data suggest phytoplankton blooms occur when growth accelerates faster than plankton-loving predators can eat. Once plankton proliferation slows, the bloom ends as predators quickly consume the entirety of the population.

Behrenfeld likens it to two rubber balls, green and red, connected by a rubber band.

"Take the green ball -- which represents the phytoplankton--and whack it with a paddle. As long as that green ball accelerates, the rubber band will stretch, and the red ball -- which represents all the things that eat or kill the phytoplankton -- won't catch up with the green ball," Behrenfeld explained. "But as soon as the green ball stops accelerating, the tension in the rubber band will pull that red ball up to it, and the red ball catches up."

The findings -- detailed in the journal Nature Geoscience -- contradict the previous understanding of plankton blooms.

Until now, scientists thought blooms begin when growth rates pass a threshold and end when they suddenly crash. The new data shows blooms begin when growth rates are still very slow but accelerating. When acceleration peaks, predators catch up and the bloom ends.

"The take-home message, is that, if we want to understand the production of the polar systems as a whole, we have to focus both on changes in ice cover and changes in the ecosystems that regulate this delicate balance between predators and prey," Behrenfeld concluded.