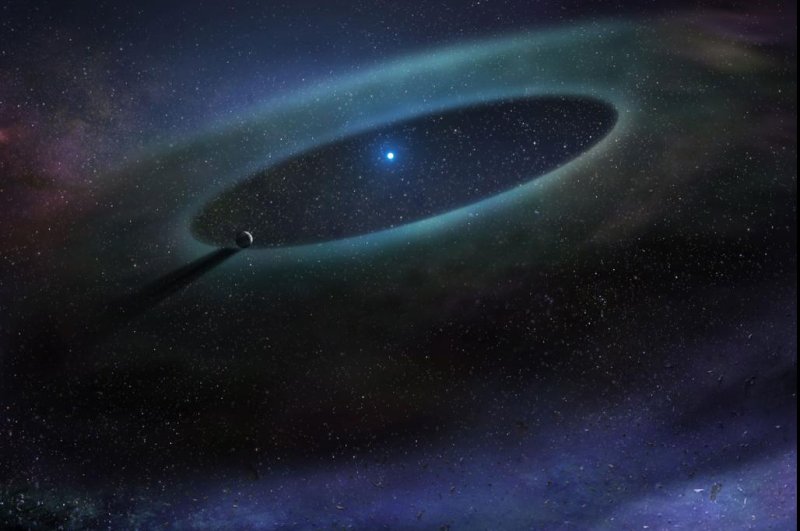

Astronomers were surprised to find larger stars had more gas in their debris disks than smaller, sun-like stars. Pictured, an artistic rendering reveals gaseous debris disk circling a star in the Scorpius-Centaurus Association. Photo by NRAO/AUI/NSF/D. Berry/SkyWorks

MIDDLETOWN, Conn., Aug. 25 (UPI) -- Recent observations made by Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, ALMA, suggest larger stars host significant carbon monoxide gas reservoirs. ALMA astronomers were surprised by the finding.

The larger the star, researchers hypothesized, the more likely radiation could have burned away any accumulated gas.

When scientists looked at the debris disks surrounding 24 star systems in the Scorpius-Centaurus Association, they found only a few of the largest stars -- roughly twice the size of the sun -- were surrounded by large amounts of carbon monoxide.

All the the smaller sun-like stars were without gas reservoirs.

"This discovery was puzzling since astronomers believe that this gas should be long gone by the time we see evidence of a debris disk," lead researcher Jesse Lieman-Sifry said in a news release.

Lieman-Sifry and his colleagues focused on stars that were relatively young, but mature enough to have formed planetary systems and debris disks. The new findings suggests large stars are able to hold on to or replenish their gas reservoirs for much longer than astronomers assumed.

The study's results -- detailed in the Astrophysical Journal -- suggest large star systems may develop gas giants much later than previously thought.

"We're not sure whether these stars are holding onto reservoirs of gas much longer than expected, or whether there's a sort of 'last gasp' of second-generation gas produced by collisions of comets or evaporation from the icy mantles of dust grains," said study co-author Meredith Hughes, an astronomer at Wesleyan University.

Researchers hope further exploration of these unique and varied gas discs will reveal the different origins of stellar gas reservoirs and how they affect planet formation.