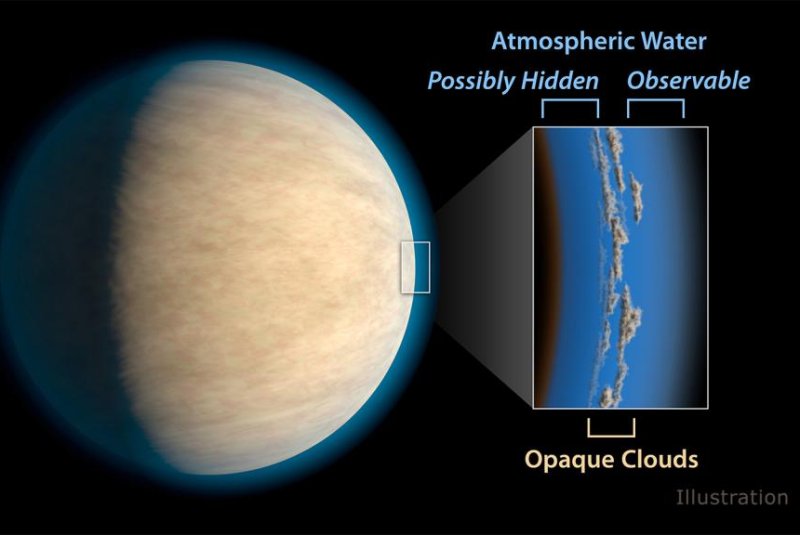

A diagram shows how layers of clouds might prevent water vapor from being detected by telescopes. Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech

PASADENA, Calif., June 8 (UPI) -- Scientists have detected water in the atmospheres of some hot Jupiters -- exoplanets the size of Jupiter, but orbiting much closer to their parent stars. Others, however, appear to be without water vapor. What gives?

New research published by scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory suggests the discrepancy may not be one at all. Layers of haze or clouds, scientists say, may simply be hiding the water from astronomers and their observatories.

Researchers came to the realization after grouping together a collection of previously studied exoplanets -- some with confirmed water vapor, others without -- and looking for commonalities. One surprising constant was significant cloud cover.

"Clouds or haze seem to be on almost every planet we studied," study leader Aishwarya Iyer, a JPL intern who is working toward a masters degree at California State University, Northridge, explained in a news release. "You have to be careful to take clouds or haze into account, or else you could underestimate the amount of water in an exoplanet's atmosphere by a factor of two."

On nearly all of the 19 surveyed exoplanets, clouds were found to have been covering more than half of the exoplanet during the original period of analysis by the Hubble Space Telescope.

"In some of these planets, you can see water peeking its head up above the clouds or haze, and there could still be more water below," Iyer said.

Researchers aren't sure what these layers of haze are composed of, but their presence is problematic for astronomers trying to peer deep into the atmospheres of faraway worlds.

Unlike rocky planets, scientists aren't looking for habitability when they study hot Jupiters. But analysis of their atmospheres can offer insight into their evolution -- whether they formed in their solar system's interior or migrated from the outskirts.

If thick haze prevents accurate analysis, however, especially cloudy hot Jupiters may be of little use to astronomers.

The new research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.