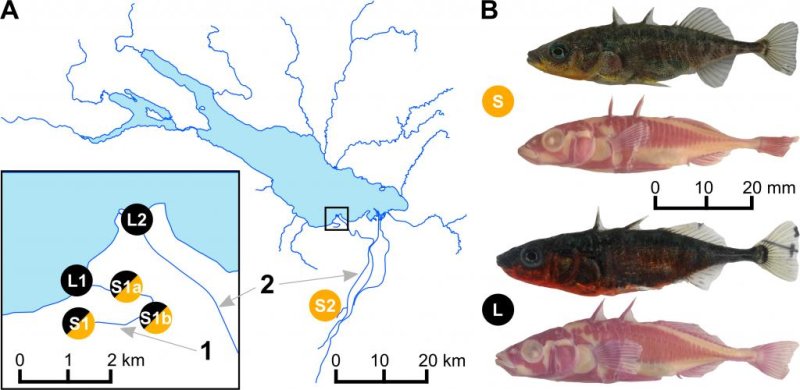

Though they live and breed in the same area -- and even interbreed -- researchers witnessed a species of stickleback fish diverging into two separate species in Switzerland's Lake Constance. Photo by Marques, et al./PLOS ONE

BERN, Switzerland, May 12 (UPI) -- New empirical evidence supports theoretical research that suggests cooperation -- not competition -- is the main driver of speciation and evolution.

The theory was developed by Roberto Cazzolla Gatti, an associate professor of ecology and biodiversity at Tomsk State University in Russia. It was inspired by the failure of Gause's principle of competitive exclusion to explain what was actually happening in ecosystems.

The principle -- which has come under attack in recent years -- states that two species competing for the same resources can't coexist in the long run, all other ecological factors being equal.

Gatti was able to show that if such a principle were true, speciation would never happen.

"In fact, if interspecific competition and the principle of competitive exclusion between different meta-populations (and then, species) were to take place, probably the coexistence of different species would never realize," Gatti explained. "We would see rather the survival of the most efficient one (which accumulates enough mutation to adapt and not to differentiate) and the extinction of the ancestor or those species belonging to other phyletic lines."

In its place, Gatti developed a new theory that suggests species coexistence and speciation is possible only if there is an avoidance of competition and genetic cooperation.

This type of speciation is called sympatric speciation. It describes the divergence of two species without any physical barriers to gene flow.

"My model predicts that the coexistence of two species in a sympatric way can happen only if there is low competition or weak competitive exclusion between them and a kind of avoidance of competition," Gatti wrote.

Recently, scientists from the University of Bern in Switzerland discovered stickleback fish splitting into two separate species in Lake Constance. Their divergence was happening fast -- and despite the fact that the fish bred in the same streams at the same time of year. The fish had been interbreeding all along, yet were splitting into two genetically and physically different species.

Gratti says the revelation is proof of the validity of his evolutionary theory. He shared his principle of cooperation in evolution in a new paper, published in the journal Biologia.

David Marques and his Swiss colleagues echoed Gratti's theory in a paper published earlier this year in the journal PLOS ONE.

"We cannot know for sure that the Lake Constance sticklebacks will continue evolving until they become two non-interbreeding specie," the researchers wrote. "But evidence for sympatric speciation is growing, from mole rats in Israel to palms on Lord Howe Island, Australia, and apple maggots evolved from hawthorn maggots in North America, leading some evolutionary biologists to think it could be surprisingly common."