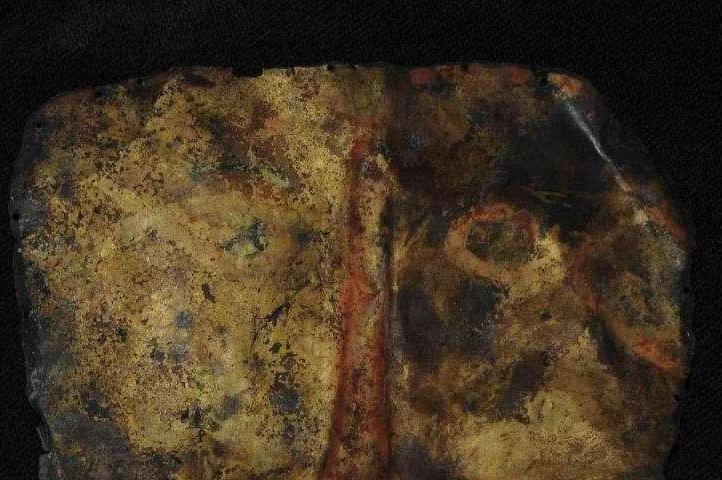

1 of 2 | Researchers recovered a gold and silver mask from ancient tombs in the Nepalese Himalayas. Photo by M. Aldenderfer

CAMBRIDGE, England, April 1 (UPI) -- Researchers have identified silk and dyes from China and India among ancient textiles recovered from dig sites in the Nepalese Himalayas. The materials have been dated between A.D. 400 and 650.

Because there's no evidence of local silk production in the region, the findings suggest the nearby village of Samdzong was incorporated into the famed Silk Road trading route much earlier than previously thought.

Samdzong is found in Nepal's Upper Mustang region, near the border dividing Nepal and China.

"The data reinforce the notion that instead of being isolated and remote, Upper Mustang was once a small, but important node of a much larger network of people and places," Margarita Gleba, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, said in a news release. "These textiles can further our understanding of the local textile materials and techniques, as well as the mechanisms through which various communities developed and adapted new textile technologies to fit local cultural and economical needs."

The archaeological record has yielded relatively few contemporary textile artifacts in Nepal, but the tomb complex found among the mountainous caves near Samdzong featured an ideal climate for preservation.

The dyed silk is one of several textile artifacts recovered from the tomb complex, where there are five tomb shafts. Some of the textiles are woven from wood fabrics and feature copper, glass and cloth beads.

On some of the fabrics, scientists at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage were able to identify lac dye sourced from India.

Researchers first began excavating the complex after it was exposed when a small earthquake sheared a mountainside cliff face.

Gleba and her colleagues shared their findings in the journal STAR: Science and Technology of Archaeological Research.