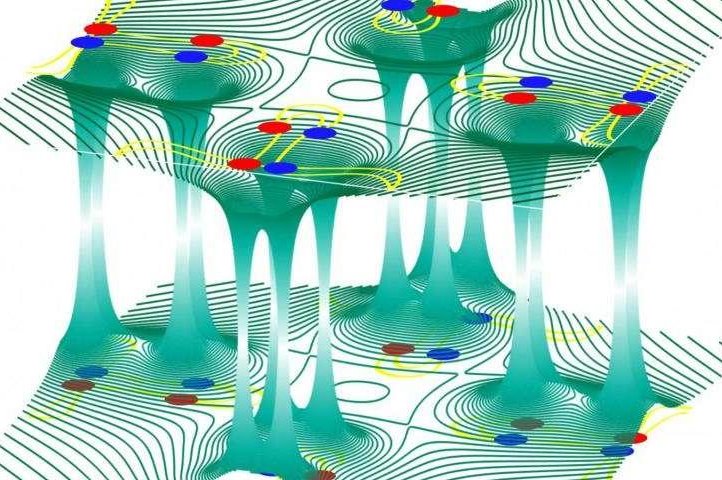

A diagram shows the unique rabbit hole-like tunnels electrons use to travel through a new type of synthetic crystal. Photo by Princeton University

PRINCETON, N.J., March 10 (UPI) -- Electrons normally travel on the surface of crystals, but a newly developed synthetic crystal features tiny tunnels through which electrons transport themselves.

"It is like these electrons go down a rabbit hole and show up on the opposite surface," Ali Yazdani, a physics professor at Princeton University, said in a press release. "You don't find anything else like this in other materials."

The crystal is made of layers of tantalum and arsenic. It is a type of material called a Weyl semi-metal, named for its contradictory qualities of both conducting and blocking electrons.

While monitoring the path of electrons across the crystals surface, researchers realized some of the electrons were disappearing into the crystal's innards. Experiments suggest the electrons can only be sucked into the so-called rabbit holes if they're traveling at the right speed and in the proper direction -- if they have the so-called Weyl momentum.

The points at which the electrons disappear are called Weyl points. Researchers believe the points come in pairs -- an entrance and exit ramp.

"It is as if you have an electron on one surface, and it is cruising along, and when it hits some special value of momentum, it sinks into the crystal and appears on the opposite surface," Yazdani reiterated.

Two scientists working in Yazdini's lab, postdoctoral researcher Hiroyuki Inoue and graduate student Andras Gyenis, used a scanning tunneling microscope to observe the waves created by the disappearing electrons. The results confused the researchers.

"Some of the interference patterns that we expected to see were missing," Yazdani said.

But in conferring with other physicists, the researchers realized the patterns made sense if the electrons were being sucked down into the crystal.

Researchers are now looking for similar electron behavior in other types of crystal. The material could be used to build speedier electronic devices, but first scientists need to find ways to study and better understand these unique conductive tunnels

The new research was published this week in the journal Science.