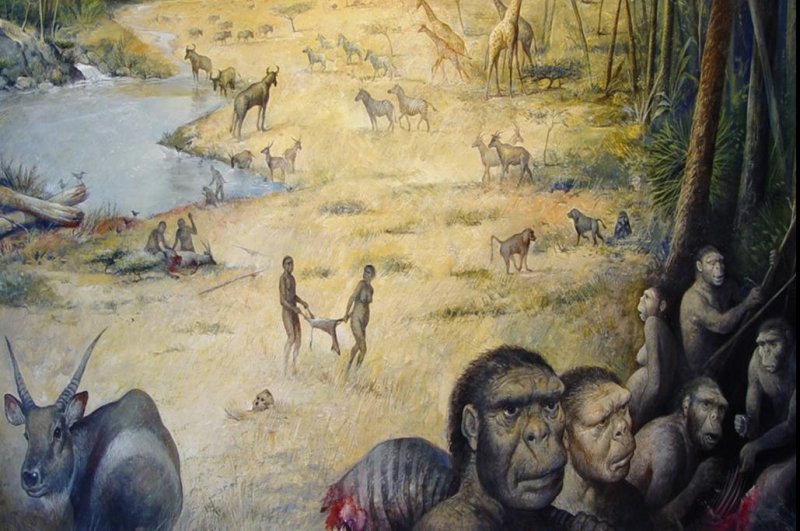

A painting depicts life for early man in Tanzania's Olduvai Gorge 1.8 million years ago. Photo by M.Lopez-Herrera/The Olduvai Paleoanthropology and Paleoecology Project/Enrique Baquedano

NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J., March 10 (UPI) -- Paleoanthropologists at Rutgers University recreated the African landscape of 1.8 million years ago to show what life was like for early humans. Surprise, it was no cakewalk.

"It was tough living," Gail M. Ashley, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Rutgers, said in a news release. "It was a very stressful life because they were in continual competition with carnivores for their food."

The newly developed model is based on the findings of paleontologists at a prolific dig site in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. First excavated in 1959, the site has yielded hominin and animal fossils, as well as stone tools.

Fossil analysis and soil samples helped Ashley and her colleagues recreate the landscape and habitat -- the plants, animals and terrain -- that surrounded the early humans that lived there.

The ancient landscape there featured a freshwater spring, wetlands, grasslands and woodlands.

"We were able to map out what the plants were on the landscape with respect to where the humans and their stone tools were found," Ashley said. "That's never been done before. Mapping was done by analyzing the soils in one geological bed, and in that bed there were bones of two different hominin species."

The site was home to two species of early humans, Paranthropus boisei and Homo habilis.

The more ape-like P. boisei was stocky and small-brained, while the more human-like H. habilis featured lighter bones and a slightly larger brain. Both stood between 4.5 and 5.5 feet tall and had an average lifespan between 30 and 40 years.

Researchers found large concentrations of bones in what were once woodlands. Scientists don't believe the hominins camped there, but brought animal carcasses there to eat in safety, surrounded by palm and acacia trees.

Researchers aren't sure whether the early humans were hunting yet, or simply scavenging carcasses killed by other predators.

Though researchers don't believe the hominins lived at the site, the combination of landscape features -- fresh water and the security of the woods -- was attractive enough that they frequented the site for thousands of years.

At one point, a nearby volcanic eruption showered the site with ash, helping to preserve the hominin and animal bones.

"Think about it as a Pompeii-like event where you had a volcanic eruption," Ashley said. "[The eruption] spewed out a lot of ash that completely blanketed the landscape."

The new research was published this week in the journal PNAS.