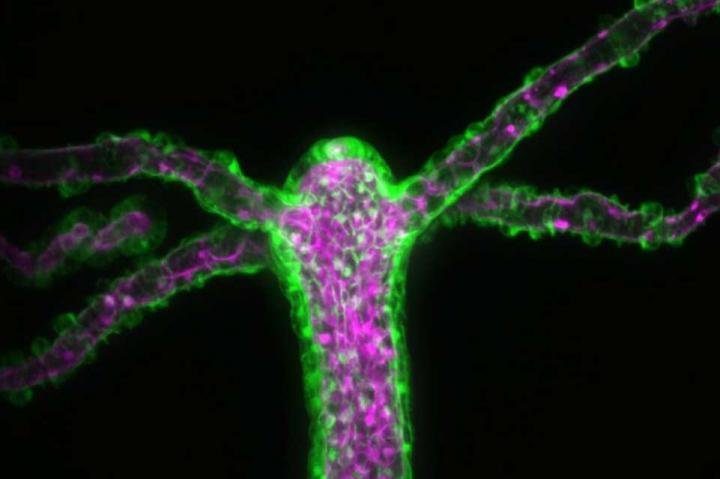

The Hydra vulgaris is pictured with its two tissue layers transgenically illuminated. Photo by Cell Press/UC-San Diego

SAN DIEGO, March 8 (UPI) -- Researchers have revealed the method by which a hydra opens its mouth to consume food. In order to open wide, the tiny freshwater animal splits apart its face.

Hydra is a genus of tiny freshwater organisms within the phylum Cnidaria -- the phylum that includes jellyfish, sea anemones and corals, among others.

Most hydra measure less than half an inch. They look like a tiny version of those zany pencil-shaped balloons that collapse and inflate in the parking lots of used car dealerships -- their arms flailing wildly.

On one end of a hydra's tube-like body is the mechanism used to affix itself to a rock or plant. On the other end is a ring of tentacles. When a small shrimp accidentally bumps into a hyrda's tentacles, the creature shoots out tiny poisonous barbs.

Scientists have previously detailed the hydra's hunting technique, but until recently, researchers hadn't paid much attention to how the hyrda actually swallows its food.

According to the new study, published this week in the Biophysical Journal, hydras peel back their facial cells to expose a black maw, or blatter, into which their prey is sucked in and consumed. Leftover, indigestible bits are spit back out the same way they came in.

By genetically engineering hydra to feature bioluminescent bilayered tissue, scientists at the University of California, San Diego were able to observe the unique movement of the hydra's facial cells during consumption.

Their observations suggest the hydra's cells don't so much move around or divide but change shape. Radial fibers pull on the cells to create an opening, similar to the way human facial muscles open and close an eyelid.

"The fact that the cells are able to stretch to accommodate the mouth opening, which is sometimes wider than the body, was really astounding," senior author Eva-Maria Collins, a biophysicist at UC-San Diego, said in a news release. "When you watch the shapes of the cells, it looks like even the cell nuclei are deformed."

Collins and her colleagues aren't sure what evolutionary advantages the peculiar facial opening offers the hydra. But they hope to find out; their research is ongoing.