Researchers are studying nuclear reactions in an effort to identify the origins of ancient stardust. Photo by MSU

LANSING, Mich., March 8 (UPI) -- Researchers at Michigan State University say dust found at meteor sites on Earth came from ancient stellar explosions and likely predate the birth of the sun.

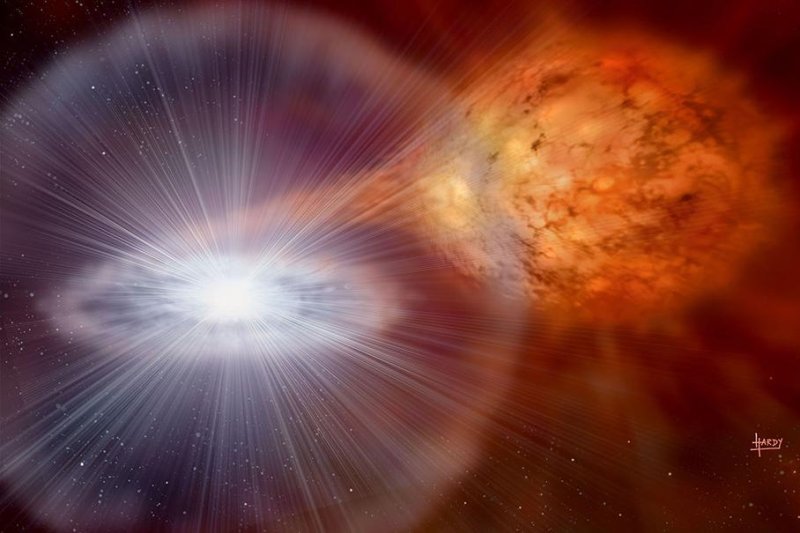

Physicists are currently studying the microscopic meteoritic material for subatomic clues as to where it came from. Specifically, scientists want to know whether the stardust was forged and expelled in a classical nova -- an explosion on the surface of the larger companion in a binary star system.

The solar system is made up of gas and dust shot into interstellar space by exploding stars. That much is certain. But identifying ancient interstellar particles is a tall task.

"There is a recycling process going on here," scientist Christopher Wrede, assistant professor of physics at Michigan States and spokesperson for the research project, explained in a news release. "When stars die, they spew out material in the form of dust and gas, which then gets recycled into future generations of stars and planets."

During a series of recent experiments, Wrede and his colleagues tested which exotic radioactive nuclei have the strongest influence on novae-produced silicon isotopes.

Isotope silicon-30 is rare on Earth but abundant in stardust. Researchers know novae produce silicon-30, but how much has remained a mystery.

The latest experiments -- as well computer models inspired by the results -- promise to expose how much and what kinds of silicon isotopes are produced in different types of supernova explosions.

"These particular grains are potential messengers from classical novae that allow us to study these events in an unconventional way," Wrede said. "Normally what you would do is point your telescope at a nova and look at the light."

"But if you can actually hold a piece of the star in your hand and study it in detail, that opens a whole new window on these types of stellar explosions."

The research is ongoing, but the latest progress was recently detailed in the journal Physical Review Letters.