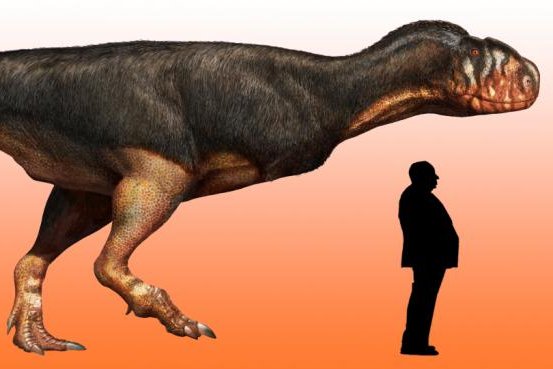

A rendering offers an idea of how large abelisaurs were. Photo by ICL

LONDON, Feb. 29 (UPI) -- After re-examining a fossilized femur bone belonging to an abelisaur specimen, researchers can say with more certainty how large these fearsome predators could become.

Based on their analysis, researchers at Imperial College London believe the femur belonged to an abelisaur weighing nearly two metric tons and stretching nine meters, or almost 30 feet. Those dimensions make it one of the largest abelisaurs ever found.

The new research was detailed in the journal PeerJ.

"Smaller abelisaur fossils have been previously found by paleontologists, but this find shows how truly huge these flesh eating predators had become," researcher Alessandro Chiarenza, study co-auhtor, said in a press release. "Their appearance may have looked a bit odd as they were probably covered in feathers with tiny, useless forelimbs, but make no mistake they were fearsome killers in their time."

Abelisauridae dinosaurs made up for their tiny forelimbs and odd appearance with massive hindquarters and deadly sharp teeth. They thrived in what is now northern Africa some 95 million years ago, though abelisaur fossils have been dated as far back as 170 million years ago and as recently as 66 million years ago.

The femur was originally found in a Moroccan deposit known as Kem Kem Beds -- famous for its abundance of predatory dino bones. The site has confounded researchers who believe it would have been impossible for so many carnivorous dinosaurs to coexist in such tight quarters.

New analysis suggests the sometimes violent geologic conditions that created Kem Kem Beds may have also mixed up the strata and chronology of the fossil record.

Other sites suggest abelisaur were inland hunters, somewhat separated from their closest cousins, who preferred to hunt fish near lakes and rivers.

"This fossil find, along with the accumulated wealth of previous studies, is helping to solve the question of whether abelisaurs may have co-existed with a range of other predators in the same region," Chiarenza explained. "Rather than sharing the same environment, which the jumbled up fossil records may be leading us to believe, we think these creatures probably lived far away from one another in different types of environments."

The fossil was not recently unearthed, but had been sitting in a museum drawer for several decades -- further proof that closeted collections hide nearly as many secrets as untouched earth.

"While palaeontologists usually venture to remote and inaccessible locations, like the deserts of Mongolia or the Badlands of Montana," added Andrea Cau, study co-author and researcher at the University of Bologna, "our study shows how museums still play an important role in preserving specimens of primary scientific value, in which sometimes the most unexpected surprises can be discovered."