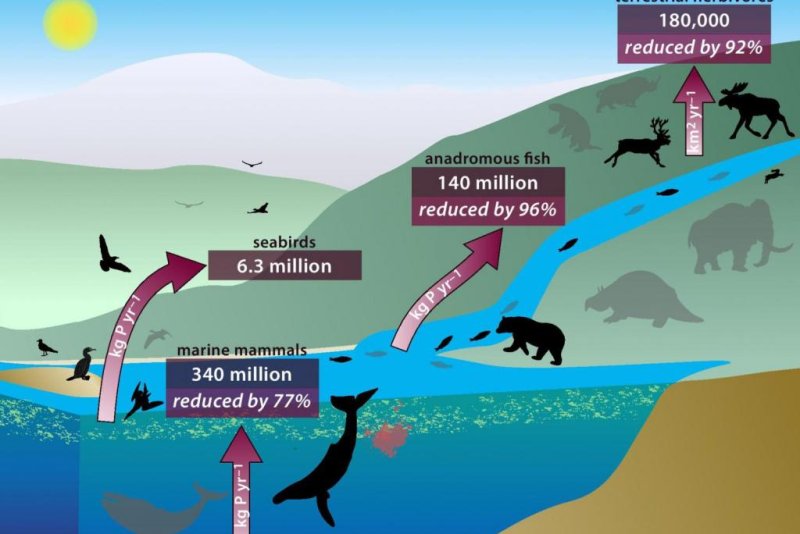

A chart reveals how the loss of wildlife diversity and the disappearance of large animals has led to a drastic reduction in the amount of recycled nutrients available on Earth. Photo by University of Vermont

BURLINGTON, Vt., Oct. 26 (UPI) -- Most of the largest animals in Earth's history are now gone -- dinosaurs, mammoths, megalodons, whales. And gone with them are their sizable bowel movements. Scientists say that's bad news for Earth's fertility.

In a new study published in the journal PNAS, scientists suggest Earth is a less productive place with fewer and fewer large predators around. Large animals on land and in the sea, researchers now realize, played an outsized role in recycling nutrients.

By eating and pooping in different places, the animal kingdom works like giant compost bin. And the largest animals, especially those that travel great distances, played an especially big role in the process.

When dinosaurs, and later large "megafauna" mammals, ruled the land and massive whales and sharks dominated the sea, the Earth's biggest species turned over a significant amount of phosphorous -- the most vital nutrient for plant growth. Today, phosphorous and other nutrients are mostly recycled by Earth's tiniest organisms, bacteria.

Microbes have always been important, but they used to have a lot more help.

"This study challenges the bottom-up bias that some scientists have -- that microbes are running the show, and phytoplankton and plants are all that matter," Joe Roman, a whale expert at the University of Vermont, said in a press release.

Scientists believe whales play an especially important role in recycling, by bringing deep sea nutrients to the surface. Fish also provide transportation by helping transfer nutrients from the ocean to fresh water upstream.

Not only are many large species now gone -- along with their recycling powers -- but the nutrients-churning species that remain are dwindling in number and range.

"This once was a world that had 10 times more whales; 20 times more anadromous fish, like salmon; double the number of seabirds; and 10 times more large herbivores -- giant sloths and mastodons and mammoths," Roman explained.

Some 300 years ago, scientists estimate up to 350,000 blue whales cruised the oceans. Today a few thousand remain. Whale populations overall have declined somewhere between 60 and 90 percent.

Whales alone once moved 750 million pounds of phosphorus from the ocean depths to the surface. Today, that number is 165 million.

"Phosphorus is a key element in fertilizers and easily accessible phosphate supplies may run out in as little as 50 years," said lead study author Chris Doughty, an ecologist at the University of Oxford. "Restoring populations of animals to their former bounty could help to recycle phosphorus from the sea to land, increasing global stocks of available phosphorus in the future."

Researchers say the best way to ensure Earth remains fertile is to better protect whales and their habitat.

On the land, large mammals have been replaced by domestic cattle. Because their movement is constrained by fences, their recycling abilities are marginal. To improve land-based nutrients recycling, true herders, grazers and foragers are needed.

Scientists say the reestablishment of bison herds in the West are an encouraging sign, but they need a lot more help.

"Recovery is possible and important," said Roman.