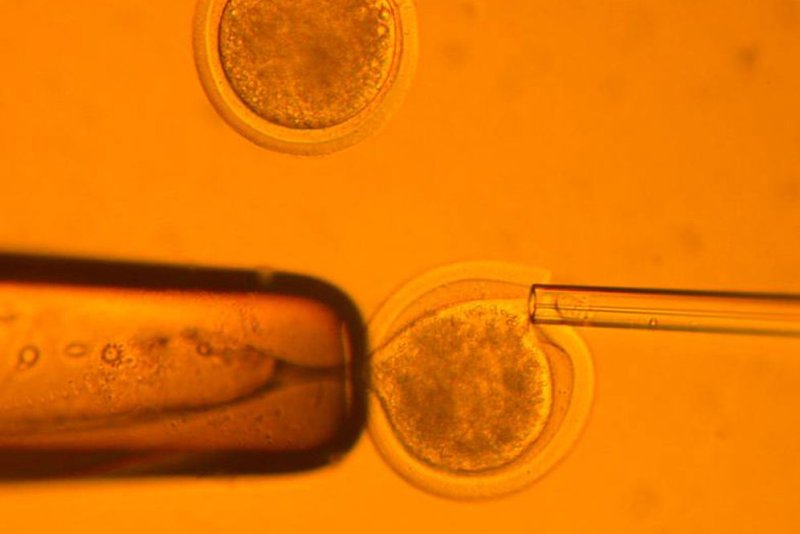

Researchers in Britain have asked permission to edit the gens of a human embryo. Scientists in South Korea recently cloned a human embryo, to the chagrin of many in the research community, while Chinese scientists successfully edited the DNA of a human embryo, this summer. Photo by UPI Photo/Woo Suk Hwang/Seoul National University |

License Photo

LONDON, Sept. 18 (UPI) -- U.K. health officials with the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority say they've received a request to genetically modify a human embryo, but have yet to review the application.

The bid comes from a team of scientists led by Kathy Niakan, a stem cell researcher at the Francis Crick Institute in London. Niakan wants permission to edit the genomes of human embryos.

Earlier this summer, when a team of Chinese scientists announced they had successfully altered the genetic code of a human embryo, disapproving grumbles echoed throughout the science world. Beneath the protests, however, was the realization that soon or later, the scientific community was going to have to face this ethical dilemma head on.

Proponents of embryonic gene editing say the new modification technology, called CRISPR-Cas9, could eventually allow researchers to eliminate genetic disorders by correcting flawed coding.

But Niakan and her colleagues don't want to birth genetically modified babies nor specifically correct gene flaws, which is illegal in the United Kingdom. They say their work will take a more general approach, in order to improve gene-editing technology and seek answers to broader questions about human embryo development.

In a statement released on institute's website, Niakin said the research would "provide further fundamental insights into early human development."

Niakin also said their planned work would be in compliance with current laws governing embryonic research, and that "by applying more precise and efficient methods in our research we hope to require fewer embryos and be more successful than the other methods currently used."

Niakin and her colleagues say their work would also have implications for stem cell technology, with application in a variety of medical fields.

But the ethics of such research remain murky within the research community.

This year, the U.S. National Institutes of Health banned funding for human embryo gene-editing research.

But in an email to NPR, George Daley, a stem cell researcher at Harvard University, said Niakin's proposed research doesn't appear to violate the International Society for Stem Cell Research's guidelines.

Those guidelines "would not preclude gene editing of human embryos for research to address critical questions in embryology, as long as the experiments are approved after a rigorous process of stem cell research oversight," Daley wrote.

Earlier this week, a group of researchers and medical ethicists, known as the Hinxton Group, released a statement in support of Niakin's research, saying such work has "tremendous value to basic research."

The main worry among researchers and ethicists is that gene-editing technology will progress faster than regulators and industry standards. And that will be a central point of debate in the coming months, as academies of science in the United States, China and Europe prepare to meet and discuss the issue.