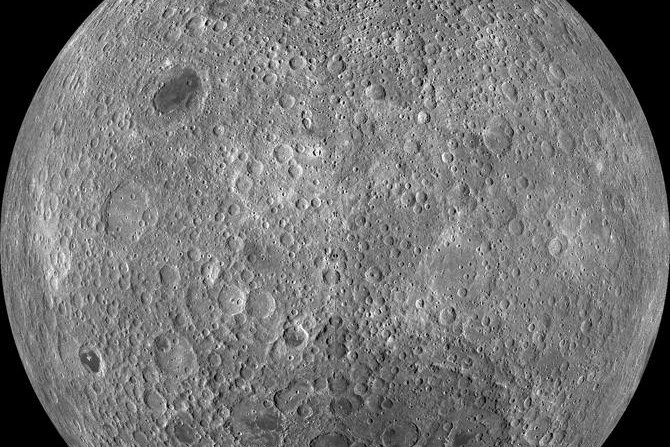

Researchers say the top layer of the moon's crust is as fractured as it can be. Photo by NASA/JPL

WASHINGTON, Sept. 10 (UPI) -- Researchers at MIT say it's impossible for the far side of the lunar surface to be any more fragmented than it already is.

Anyone who has seen the moon knows it is scarred by craters -- and that is only its front side. The far side, the side Earthlings never see, is even more battered.

Scientists say most of the moon's drubbing took place four billion years ago, during what's been dubbed the Late Heavy Bombardment. So many asteroids hit the moon that the upper layer of the lunar crust, the megaregolith, became saturated with fragmentation.

Researchers want to know more about the moon's fragmentation, because the opening up of the lunar curst may offer clues as to how pores within the Earth first formed and encouraged the development of early life forms.

"The whole process of generating pore space within planetary crusts is critically important in understanding how water gets into the subsurface," Jason Soderblom, a research scientist in MIT, said in a press release. "On Earth, we believe that life may have evolved somewhat in the subsurface, and this is a primary mechanism to create subsurface pockets and void spaces, and really drives a lot of the rates at which these processes happen. The moon is a really ideal place to study this."

But because the moon's upper surface layers are so heavily battered, fragmented as much as possible, newer impacts can have the opposite effect of making the megaregolith less porous. This makes it difficult to model what the Late Heavy Bombardment may have looked like, as the history of post-saturation impacts are essentially a wash.

To get around the problem, Soderblom and colleagues are comparing the porosity of the top surface to deeper layers of the moon's crust -- layers not quite as badly beaten.

The scientists are able to trace larger, deeper impacts by analyzing the details of moon's gravity field -- data captured by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory.

"For the smaller craters, it's like if you're filling a bucket, eventually your bucket gets full, but if you keep pouring cups of water into the bucket, you can't tell how many cups of water beyond full you've gone," Soderblom explained. "Looking at the larger craters at the subsurface might give us insight, because that 'bucket' isn't full yet."

Soderblom hopes these deeper craters offer some perspective on how the top surface's smaller craters came to be -- a snapshot of what the Late Heavy Bombardment might have looked like.

"What we really hope to do is to figure out the number of impacts in the range of 100 kilometers in diameter, and from that, we can extrapolate to the smaller craters, assuming different populations of impactors, and those different assumptions will tell us where the impactors came from," Soderblom added. "This will help to understand the origin of the Late Heavy Bombardment, and whether it was disrupted material from the asteroid belt, or if it was further out."