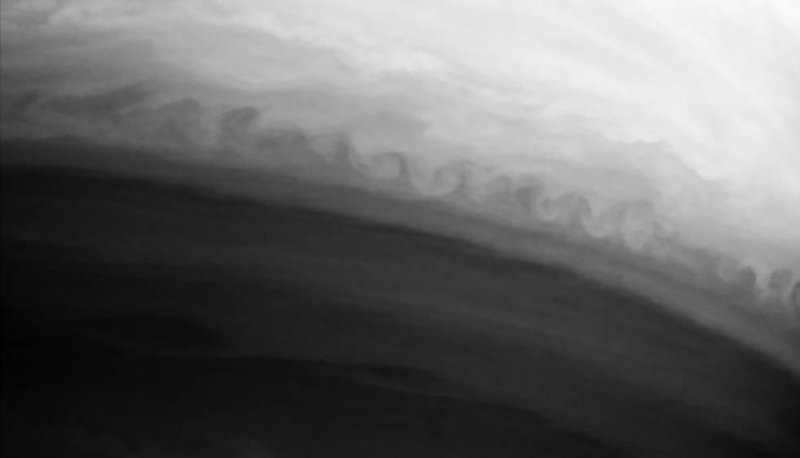

The surfer-shaped waves are found in Saturn's atmosphere too, as captured by NASA's Cassini mission. Photo by NASA

GREENBELT, Md., July 8 (UPI) -- Kelvin-Helmholtz waves are everywhere. They're at the beach, deep below the ocean surface, in the clouds -- and also in space.

Researchers have located the waves, recognizable for the rising curl familiar to surfers, on the boundaries of near-Earth space, where -- until recently -- scientists didn't believe they occurred, at least not regularly.

"We have known before that Kelvin-Helmholtz waves exist at the boundaries of Earth's magnetic environment -- but they were considered relatively rare and thought to only appear under specialized conditions," Shiva Kavosi, a space scientist at the University of New Hampshire, said in a press release. "It turns out they can appear under any conditions and are much more prevalent than we thought. They're present 20 percent of the time."

Kavosi is the author a paper on the space waves that was published early this year. But a new paper goes further, offering a possible explanation for their regularity. Researchers at Boston University and Virginia Tech suggest the space waves are caused by a plume of charged gas expelled by Earth's plasmasphere. Their hypothesis is detailed in a new paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

In analyzing data collected by NASA's THEMIS mission, a five-satellite effort to study the magnetosphere, researchers noticed a plasmasphere gas plume contacts the edge of the magnetosphere just prior to the appearance of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves.

The arrival of the plume's charged gas particles may trigger a denser, slower layer along the magnetosphere boundary, while faster solar winds descend from above -- the ideal combo for Kelvin-Helmholtz waves.

The ubiquitous toppling waves require difference in velocity and tension in the waves' various layers. That's what gives the waves their surf-shaped curve.

"The theory of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves is well-developed, but we don't have many observations," said Evan Thomas, a student at Virginia Tech who has been conducting research at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "These new observations show that the waves are happening more often than expected and are probably more important than we thought -- but we still don't know all the details."