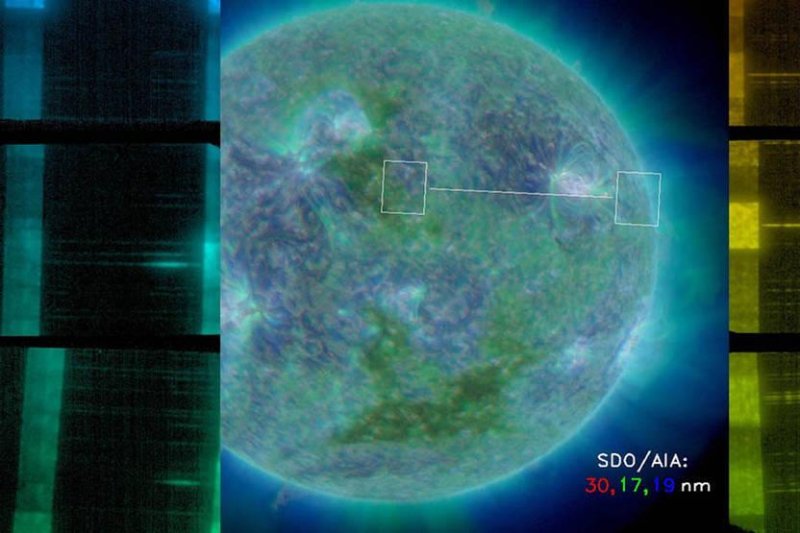

An image shows how NASA's spectrograph instrument can differentiate between the varying light wavelengths of material at extremely high temperatures. Photo by NASA/EUNIS/SDO

INDIANAPOLIS, April 29 (UPI) -- The sun's atmosphere is 300 times hotter than its surface. The strange phenomenon, called coronal heating, has long befuddled scientists.

Why, scientists asked, is the surface of the sun only 10,340 degrees Fahrenheit, while its atmosphere is more than 3 million degrees Fahrenheit? Typically, material gets cooler as it moves away from the heating source.

Now, there are some answers. New research suggests the sun's atmosphere is heated by explosive bursts of heat -- tiny explosions called nanoflares -- not gradual convection. The evidence was presented on Wednesday by scientists at the inaugural Triennial Earth-Sun Summit, or TESS, a science convention held this week in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The convention is being attended by scientists and research groups whose work touches on the interplay between Earth and sun.

"The explosions are called nanoflares because they have one-billionth the energy of a regular flare," explained Jim Klimchuk, a solar scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and one of the presenting researchers.

"Despite being tiny by solar standards, each packs the wallop of a 10 megaton hydrogen bomb," Klimchuk added. "Millions of them are going off every second across the sun, and collectively they heat the corona."

Researchers studied the phenomenon using an instrument designed to measure concentrations of mass at high temperatures. The instrument, called a spectrograph, was installed on a plane and flown at high altitude while it imaged solar activity.

The spectrograph was able to render tiny flashes of heat -- measuring upwards of 18 million degrees Fahrenheit -- as a series of wavelengths, revealing the nanoflares that were otherwise invisible. Coupled with X-ray imaging by the NuSTAR space telescope, the new nanoflare data offers the best yet explanation for coronal heating.

Scientists at the meeting say the new evidence is only the beginning, however, and that the revelations will lead to further insights into the little understood interplay between the different regions and layers of the sun, its atmosphere and the space that surrounds it.