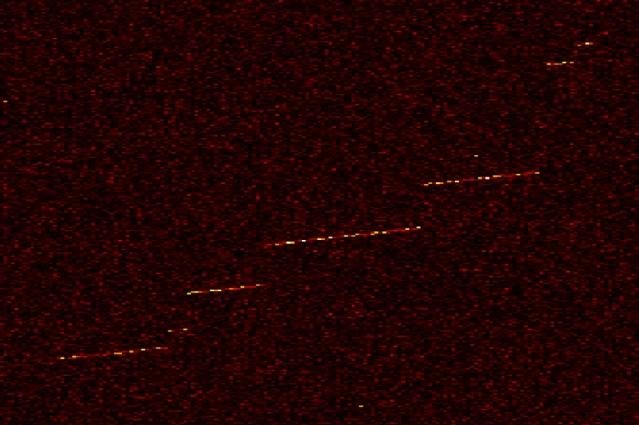

The 2-D representation of the frequency jumps or chirps as the trapped electrons bump into the residual gas atoms. Photo by MIT

BOSTON, April 22 (UPI) -- The Large Hadron Collider is the largest particle collider in the world. Its circular tunnel boasts a 17-mile circumference to accelerate particles toward collision inside a detector. The latest particle detector from the labs of MIT is not much bigger than a coffee cup.

The tabletop particle detector isn't capable of smashing atoms at high speeds, of course, but it can detect electrons. And researchers suggest the magnet-based device may be able to detect neutrinos.

The detector uses a magnet to siphon off electrons from decaying gas, trapping them in a magnetic bottle. A radio antenna inside measures and maps the minute movements of the electrons.

Researchers recently used the device to observe the behavior of more than 100,000 electrons from decaying krypton gas.

"We can literally image the frequency of the electron, and we see this electron suddenly pop into our radio antenna," Joe Formaggio, an associate professor of physics at MIT, explained in a press release. "Over time, the frequency changes, and actually chirps up. So these electrons are chirping in radio waves."

Each electron "chirps" as it bumps into other atoms trapped in the detector. The sequence of chirping frequencies can reveal the patterned movement of the electrons.

Researchers believe the detector could also pick up the presence of neutrinos.

Neutrinos are theoretical subatomic particles that are neutrally charged and are seemingly impossible to detect because they don't interact with other particles.

Scientists at MIT believe their device could detect a neutrino by measuring the decaying energy of tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. When tritium decays, it turns into an isotope of helium and, as a byproduct, expels an electron and a neutrino.

The laws of particle physics suggest the energy of expelled particles adds up to the original energy of the parent neutron. By measuring the energy of electrons given off by decaying tritium, researchers believe they'll be able to deduce the mass of a neutrino.

Researchers have already established theoretical limits for the neutrino's mass, but they don't have direct evidence.

"We have [the mass] cornered, but haven't measured it yet," Formaggio says. "The name of the game is to measure the energy of an electron -- that's your signature that tells you about the neutrino."

Formaggio and his colleagues believe their new detector gives them a chance to capture that signature.

But while neutrino experts are encouraged, they say the device will need to be improved. First, its particle-holding cell will need to enlarged to hold more tritium. Researchers must also do the difficult work of tuning an extra-sensitive radio antenna to the precise frequency.

"This was the first step, albeit a very important step, along the way to building a next-generation experiment," said Steven Elliott, a technical staff member at the Los Alamos National Laboratory who did not contribute to the research. "As a result, the neutrino community is very impressed with the concept and execution of this experiment."

The particle detector is detailed in the latest issue of the journal Physical Review Letters.