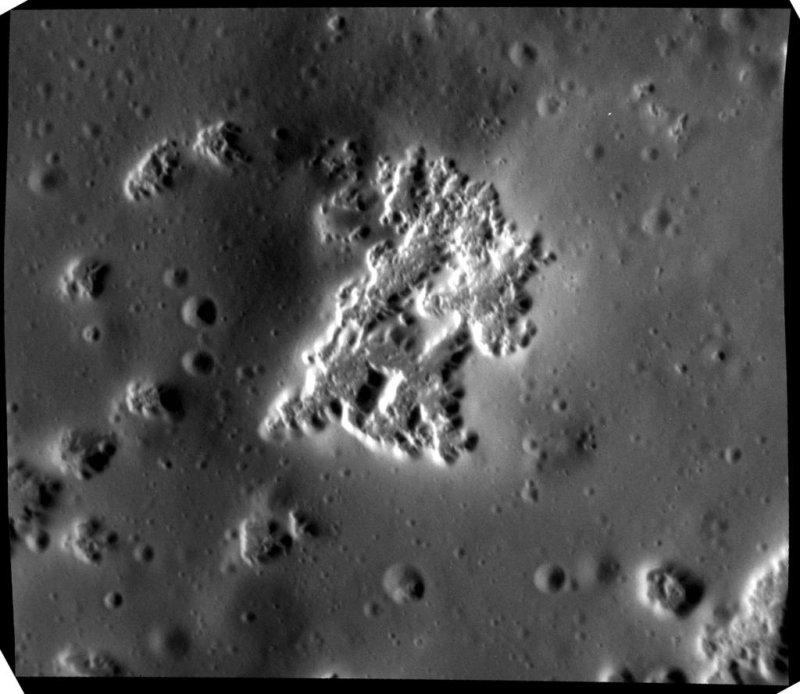

1 of 5 | This high-resolution view shows hollows on the southwestern peak ring of Mercury's Scarlatti basin. The hollows are the irregularly shaped, flat-floored depressions. Though there are many small impact craters on the surface surrounding the hollows, there are few if any within the hollows themselves. This suggests the hollows must be very young relative to the rest of Mercury's surface. NASA/Messenger/UPI

WASHINGTON, March 17 (UPI) -- Newly returned data and imagery from NASA's Messenger probe (technically, the MESSENGER probe) has allowed scientists their most detailed understanding yet of Mercury's geologic makeup. The high resolution data has also offered scientists their best views of ice deposits inside the planet's polar craters.

While Mercury is the closest planet to the sun, it hosts the thinnest of atmospheres; most of its gases are burned off by the sun's relentless rays. Unable to trap heat, the portions of Mercury's surface that don't see the sun (like the deep pits of polar craters) feature extremely low temperatures, enabling the existence of frozen water.

"We're seeing into these craters that don't see the sun, at higher resolution than was ever possible before," Nancy Chabot, the instrument scientist for Messenger's Mercury Dual Imaging System, told attendees on Monday at the Lunar and Planetary Science conference.

"Acquired with the broadband filter of MDIS, low-altitude images show that the deposits have sharp, well-defined boundaries and are not disrupted by small, young impact craters," Chabot explained in a press release. "These characteristics indicate that the deposits are geologically young. This inference points either to delivery of volatiles to Mercury in the geologically recent past or to an ongoing process that restores the deposits and maintains the sharp boundaries."

In addition to observing the ice deposits on Mercury's north pole, Messenger's instruments have also enabled the most comprehensive maps of the planet to date. Using data sent back by the probe's X-ray spectrometer and gamma-ray spectrometer, scientists have constructed full-scale maps of Mercury's entire surface.

The maps reveal never before studied geologic features, as well as provide new details on the planet's chemical makeup. Specifically, these maps reveal never-before-seen terranes, or distinct crustal blocks, that preserve unique geochemical ratios -- combinations of silicon, magnesium, sulfur and calcium.

The sizes and locations of the various terranes have allowed scientists to better understand how the planet's volcanic and tectonic processes shaped the planet's surface -- pinpointing fault fragments and the locations of ancient volcanic plains.

The large variance among the geochemical makeup of Mercury's surface, as revealed by the newly mapped terranes, also suggests Mercury's insides are equally varied in elemental composition.

"The crust we see on Mercury was largely formed more than 3 billion years ago," said Larry Nittler, deputy principle investigator of the Mercury mission. "The remarkable chemical variability revealed by Messenger observations will provide critical constraints on future efforts to model and understand Mercury's bulk composition and the ancient geological processes that shaped the planet's mantle and crust."

The new insights into the planet's elemental makeup were detailed in two scientific papers published this week.

The Messenger probe has spent the last several weeks orbiting Mercury at an intimate distance. The probe is gathering the last of its scientific observations before it abandons its orbital path and crashes into Mercury's surface -- ending its four-year mission with a bang.

Despite the probe's forthcoming suicide, scheduled for April 30, the rich mass of data it has collected and beamed back to Earth will keep NASA scientists busy for years to come.