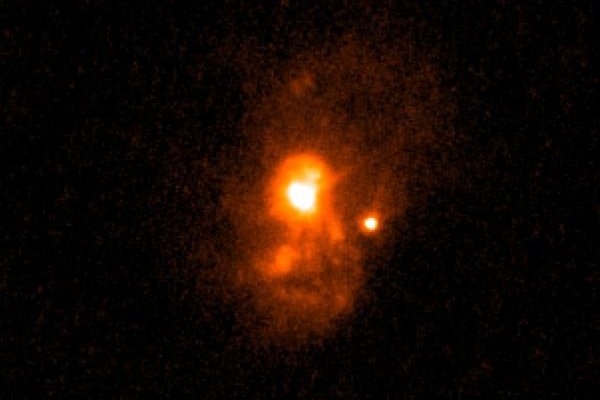

A newly discovered galaxy is helping scientists understand how the universe first became illuminated. (Hubble Telescope/ESA/NASA)

BALTIMORE, Oct. 10 (UPI) -- The early universe was dark, very dark. For almost 400 million years, it remained dark. Until the first star-producing galaxies began putting out enough ultraviolet light to illuminate the cosmos.

But astronomers still aren't entirely sure how the process of illumination came about. Nearly 400,000 years after the Big Bang, the protons and electrons that had exploded out in all directions cooled and began forming the first atoms of hydrogen. The result was dense walls of hydrogen, which combined with clouds of cosmic dust to absorb early ultraviolet radiation and prevent light from traveling very far from its origin.

At some point, ultraviolet photons strong enough to rip the electrons and protons of these hydrogen atoms apart, "reionizing" the gas and turning what were previously light barricades into conductors of light -- thus lighting up the formerly dark universe.

Then, a few hundred million years later, the radiation from those multiplying stars and galaxies ripped the electrons from the protons, "reionizing" the hydrogen gas. But no one knows exactly how that happened.

But how did these high energy photons escape? Recently, researchers -- with the help of the Hubble Telescope -- located a faraway galaxy that's helping them understand the birth of light.

"The mystery was, how did these photons of this specific energy leave their galaxies?" Sanchayeeta Borthakur, a researcher at John Hopkins University, recently told The Telegraph. "Most of these photons would be expected to be absorbed by the cold and dense gas clouds where the stars are formed."

But while only one percent of the generated ultraviolet radiation escapes today's star-producing galaxies -- not nearly enough to reionize the universe's thick clouds of hydrogen -- a newly discovered galaxy named J0921+4509 allows more than 20 percent of its ultraviolet radiation to sidestep the resident dust clouds and make its way into intergalactic space. The galaxy, scientists say, is a clue as to how the universe's earliest galaxies likely behaved.

"The small size of the star-forming region helps winds from the young stars create gaps in the cloud cocoon that allows the photons to zip past and escape into intergalactic space," explained Borthakur, speaking of J0921+4509.

Borthakur likens the gaps in the clouds to the holes in swiss cheese. Without swiss cheese galaxies, the universe would have remained dark.

"Imagine the first stars turning on and within a few hundred million years, their radiation had ionised all the gas between galaxies in the Universe, ending the dark ages and beginning the era where galaxies and stars transformed the entire universe," Borthakur told Australia's ABC.

The work of Borthakur and her colleagues in analyzing J0921+4509 was recently detailed in the journal Science.