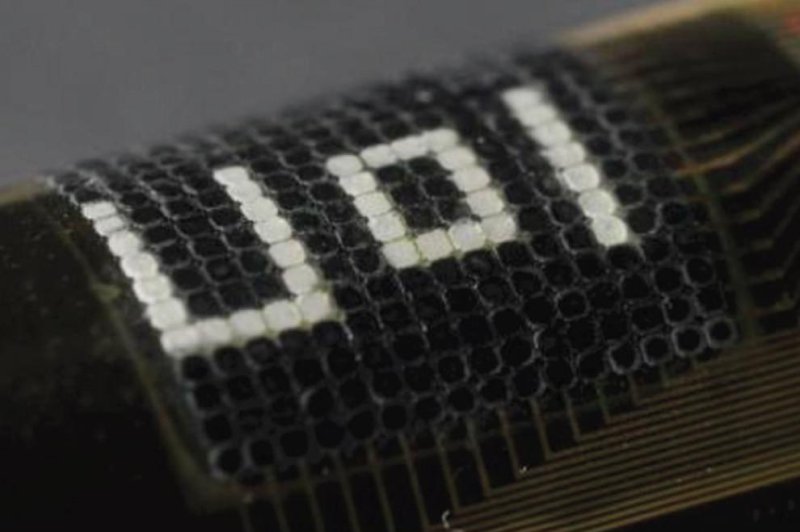

The layered color-changing skin of the new device spells out UOI, for University of Illinois. (Yu/PNAS)

WASHINGTON, Aug. 18 (UPI) -- Octopuses, squid and cuttlefish -- known collectively as cephalopods -- posses the most impressive camouflage capabilities in the natural world. Their skin can change color, shape and texture in the blink of an eye, adapting to new surroundings on the fly.

Now, those capabilities have been replicated in the lab -- or at least some of them. Scientists recently unveiled a new device, a thin and flexible pixellated sheet, that can change colors in response to its environs. The sheet was designed by materials scientists Cunjiang Yu, from the University of Houston, and John Rogers, from the University of Illinois at Urbana. Their work was assisted by marine biologist Roger Hanlon, from the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

"Our device sees color and matches it," Rogers said in a released statement. "It reads the environment using thermochromatic material."

The device is layered, featuring a light-detecting sheet at the bottom, with a silver layer above that gives the pliable skin-like device its shiny white base. Above that sits a sheet of diodes that heats overlying dye. The dye appears black at low temperatures and clear at high temps. It's all mounted on a flexible base.

"There are analogies between layers of our system and those in the cephalopod skin, but all the actual function is achieved in radically different ways," Rogers told National Geographic. "The multi-layer architecture works really well, though. Evolution reached the same conclusion."

Though the device and nature reached similar conclusions, the device is nowhere near as powerful or impressive as the real thing. For starters, it can only switch between black and white. And because it requires heat to change color, the device is comparatively slow, uses a lot of (too much) power, and reacts to only a narrow range of temps.

"Real cephalopods are capable of levels of active camouflage orders of magnitude more sophisticated than our system," Rogers told Popular Mechanics. "But we hope to eventually design manmade systems that rival those we see in biology."

The device was funded by the Office of Naval Research, and Rogers and his colleagues say the most obvious application for this technology is some sort of military camouflage function. The device is detailed in the latest edition of the journal PNAS.