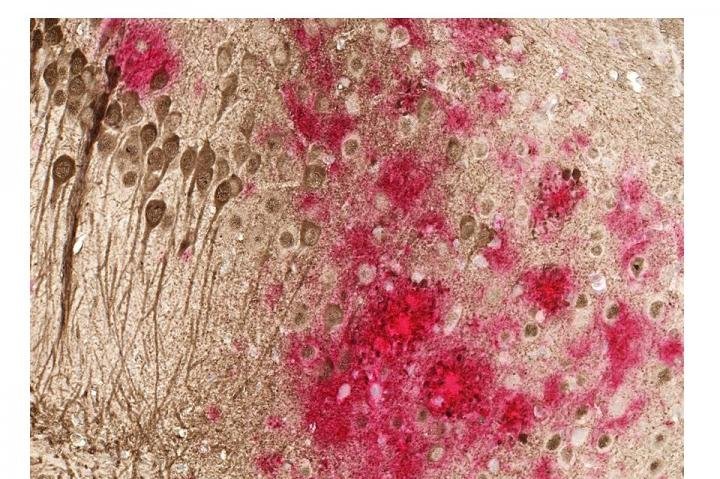

A new DNA vaccine suppresses the build up of two types of toxin proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease, a study finds. Photo by UT Southwestern

Nov. 21 (UPI) -- A new DNA vaccine suppresses the buildup of two types of toxin proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease, a study finds.

A new University of Texas Southwestern study published in Alzheimer's Research and Therapy shows that a vaccine with DNA coding injected into lab mice reduced buildup of beta-amyloid by 40 percent and tau by 50 percent. Alzheimer's contains both of those proteins.

"This study is the culmination of a decade of research that has repeatedly demonstrated that this vaccine can effectively and safely target in animal models what we think may cause Alzheimer's disease," Roger Rosenberg, founding Director of the Alzheimer's Disease Center at UT Southwestern and a study co-author, said in a statement. "I believe we're getting close to testing this therapy in people."

The vaccine also gave off an immune response, Rosenberg said, that could be safe for humans.

Past research showed antibodies could push back amyloid buildup accumulation in the brain, but this new work proved that Rosenberg could safely inject them into the body.

Rosenberg and his team of researchers think if amyloid and tau do actually cause Alzheimer's, then decreasing their presence in the human brain could provide a drastic therapeutic value.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5.7 million people have Alzheimer's, the degenerative disease that leads to death by destroying the brain's neurons. Experts expect that number to double by 2050.

Although no effective treatment for Alzheimer's exists, the discovery from the UT Southwestern team is one of a few promising vaccines designed to keep the brain safe from amyloid and tau.

"If the onset of the disease could be delayed by even five years, that would be enormous for the patients and their families," Doris Lambracht-Washington, professor at UT Southwestern and the study's senior author, said in a statement. "The number of dementia cases could drop by half."

"The longer you wait, the less effect it will probably have," Dr. Rosenberg said. "Once those plaques and tangles have formed, it may be too late."