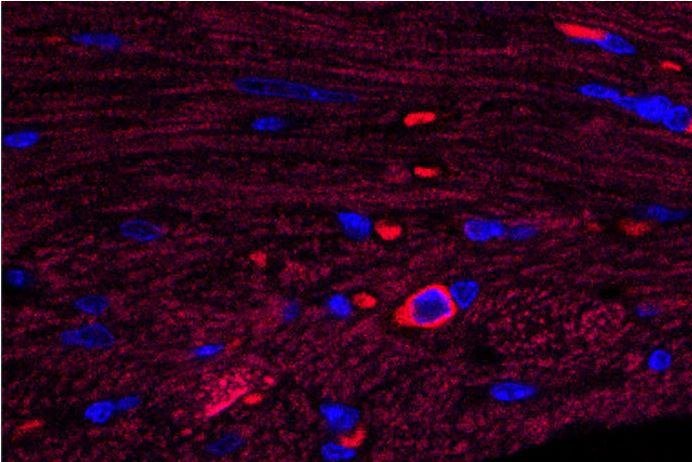

In this image of heart tissue, a single cardiac B cell lymphocyte is visible -- blue surrounded by bright red. This type of immune cell triggers damaging inflammation after a heart attack, according to researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Photo by

Lora Staloch/University of Washington

June 7 (UPI) -- Researchers have figured out why inflammation damages the heart after a heart attack and have found a way to control the decay with a drug already approved for another condition.

A type of immune cell tries to heal the injured heart but instead triggers inflammation, leading to even more damage, according to research from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis published Thursday in the journal JCI Insight.

About 735,000 Americans have a heart attack each year and about 610,000 die of heart disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Researchers hope to cut the deaths down by reducing the progression to heart disease after heart attacks.

In the study, mice lived longer if given pirfenidone, a drug already approved to treat an unrelated lung condition. In the heart, they found the drug regulates the specific response of B cell lymphocytes.

Because the drug can have side effects such as nausea and vomiting, the Washington researchers want to improve it. With support from Washington University's Office of Technology Management, they have launched a startup company focused on developing a new version of pirfenidone.

"If we understand how pirfenidone works to reduce inflammation, we can work to modify the drug or make an even better drug that may be able to help a large number of patients," author Dr. Douglas L. Mann, director of the university's Cardiovascular Division and cardiologist-in-chief at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, said in a news release.

Pirfenidone has been treated for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is when lungs are scarred for no known cause.

Because the drug also has been known for its heart-protective effects after heart attacks in mice, researchers assumed that pirfenidone's protective action in the heart was why it helps in lung disease.

"That this drug also protects the heart is not new," said author Dr. Luigi Adamo, a clinical fellow in cardiology. "But in our studies, pirfenidone didn't physically reduce scar tissue in the heart. The scar tissue is still there, but somehow the heart works better than expected when exposed to this drug. It wasn't clear why."

To determine why it happens, they reverse engineered the drug to see how it may be working.

"Since scar tissue was still present, we suspected inflammation was the main culprit in poor heart function after a heart attack," Adamo said.

When a person survives a heart attack, the body tries to heal the dead muscle by forming scar tissue. However, the scar tissue can further weaken the heart, and more damage occurs when the immune cells try to heal the injured heart and instead increase inflammation.

Most immune heart studies have focused on other types of immune cells, including macrophages, T cell lymphocytes, neutrophils and monocytes. Yet, they found found no differences in the numbers of such immune cells in the injured hearts of mice that received pirfenidone compared with those without.

But when they measured B cells, they saw a big difference.

"Our results showing B cells driving heart inflammation was quite unexpected," Adamo said. "We didn't know that B cells have a role in the type of heart damage we were studying until our data pushed us in that direction. We also found that there isn't just one type of B cell in the heart, but a whole family of different types that are closely related."

When the researchers removed these cells, the drug's benefit also went away. So, they do some good.