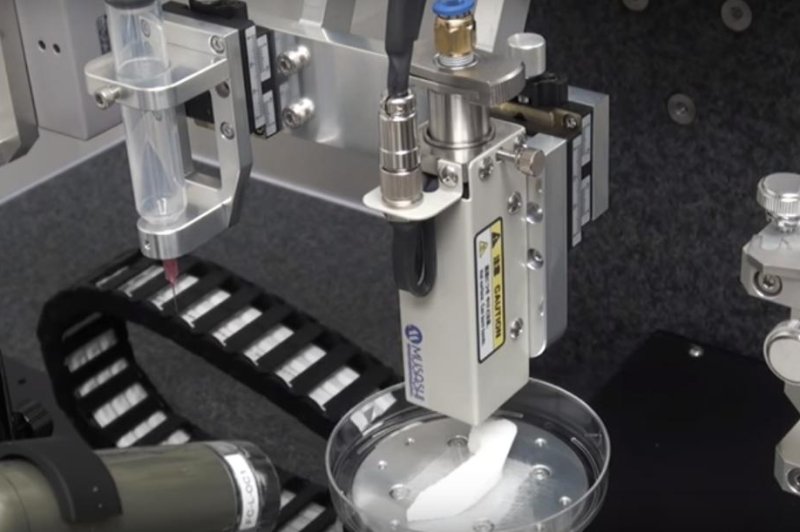

Researchers designed a 3D-printer that combines several processes to create tissues such as a jawbone, seen above, that include micro-channels to allow for the natural formation of blood vessels after they are implanted in a patient. Photo by

Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C., Feb. 15 (UPI) -- Scientists at Wake Forest University report they found a way to print bone, muscle and cartilage tissue that allows blood to flow and cells to stay alive -- an advance that may lead to the ability to print living tissues for implantation in patients.

The Integrated Tissue and Organ Printing System, developed during the last decade at Wake Forest's Institute for Regenerative Medicine, uses plastic-like materials to shape the tissues and water-based gels to deliver living cells to the tissues, according to a press release.

Although there have been some successful uses of 3D-printed body parts -- a cancer patient received ribs printed using titanium -- progress has been made on methods of printing whole organs, and scientists in England have created scaffolds that allow for the regrowth of bones.

The big challenge, researchers say, is creating channels that become veins and arteries, allowing blood to flow through tissues and cells to stay alive, which Dr. Anthony Atala, director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at Wake Forest University, told STAT has been "the basic limitation of this field forever, up to this point."

The method described by Wake Forest scientists in the new study, published in Nature Biotechnology, may have solved the issue.

They used bio-degradeable plastic to form the tissue's shape and water-based gels that contain cells, as well as a temporary outer structure to maintain shape of the tissue being printed. Rather than attempting to create a series of channels for blood to flow through, the scientists designed the printer to leave a series of micro-channels that allow nutrients and oxygen to flow through the growing tissue once implanted and develop a system of blood vessels on its own.

To test the method, the researchers printed an ear-shaped peice of cartilage, a muscle, and a piece of jawbone, allowing them to fully develop around the plastic scaffolds, and then implanted them into mice. In periods ranging from weeks to five months, the researchers found the tissues vascularized, continued developing, and appeared healthy in the mice.

"Our results indicate that the bio-ink combination we used, combined with the micro-channels, provides the right environment to keep the cells alive and to support cell and tissue growth," Atala said.

None of the printed body parts of been tested with humans yet -- safety tests and clinical trials have not been done, but researchers said further research will focus on proper development of tissues and function of tissues once they are fully grown and implanted in patients.

"Future development of the integrated tissue-organ printer is being directed to the production of tissues for human applications, and to the building of more complex tissues and solid organs," Atala told Quartz. "When printing human tissues and organs, of course, we need to make sure the cells survive, and function is the final test. Our research indicates the feasibility of printing bone, muscle, and cartilage for patient. We will be using similar strategies to print solid organs."