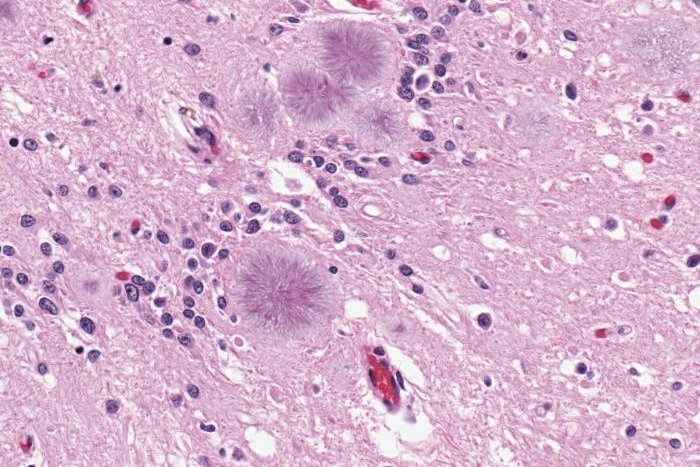

Prion infections like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease leave the brain with holes, appearing spongy. Photo by CDC/ Teresa Hammett

LONDON, June 14 (UPI) -- In the late 1950s, some 2 percent of the Fore tribe from Papa New Guinea died each year from a rare neural disease known as kuru. The mad cow-like disease was spread by the tribe's now-retired practice of eating the brains of their deceased relatives.

A new study, however, has identified a gene adaptation that protected a small subset of the Fore population from kuru and other similar diseases.

Kuru and other similar diseases are characterized by the proliferation of misshapen neural proteins called prions. These invaders stick together in infected brains, forming plaque-like polymers that slowly suffocate neural pathways and chew holes in the brain.

Scientists believe prion-like plaques play a similar role in the development of other neural diseases like Alzheimer's. And it's possible, researchers say, that similar genetic mutations could guard against a wide variety of dementias.

The gene mutation that provides kuru survivors with immunity is called V127. Researchers at University College London replicated the mutation in mice and found that it also protected them against kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (the human version of mad cow disease).

"From the human genetic work the unit has carried out in Papua New Guinea, we were expecting the mice to show some resistance to disease," lead researcher Dr. Emmanuel Asante said in a press release. "However, we were surprised that the mice were completely protected from all human prion strains. The result could not have been clearer or more dramatic."

Researchers say eating brains didn't cause the prion-resistance gene to proliferate. The kuru outbreak simply offered those with the mutation an evolutionary advantage, serving to highlight the mutation's role in safeguarding the brain.

"This is a striking example of Darwinian evolution in humans -- the epidemic of prion disease selecting a single genetic change that provided complete protection against an invariably fatal dementia," explained researcher John Collinge.

The work of Asante, Collinge and their colleagues was recently detailed in the journal Nature.