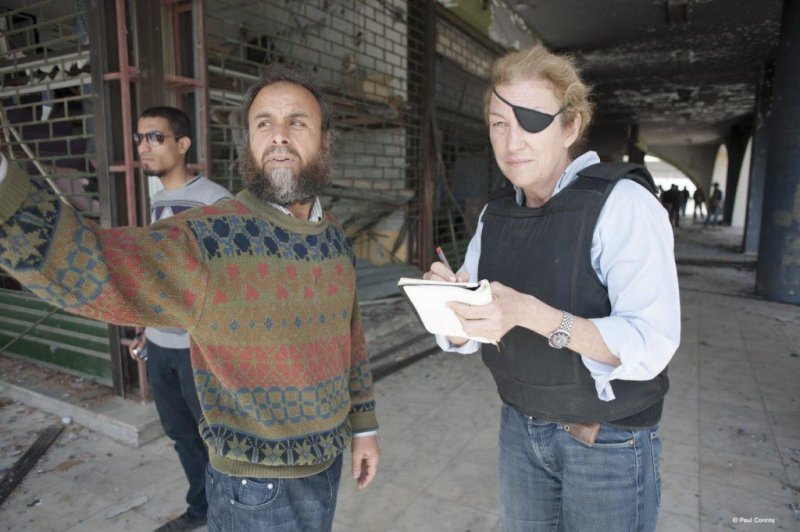

Marie Colvin lost her left eye after being struck by a rocket-propelled grenade in Sri Lanka. File Photo by Paul Conroy

Oct. 30 (UPI) -- When Marie Colvin began her journalism career in New Jersey, she was far from the danger she would find herself in while working as a war correspondent. Her early colleagues knew she had a hunger to work abroad and that she wouldn't stay stateside for long.

As a war correspondent for Britain's The Sunday Times, Colvin died in February 2012 while reporting on the Syrian civil war. A movie about Colvin's later career, A Private War, is set to hit U.S. theaters Friday.

The explosion that killed her wasn't Colvin's first brush with danger on the job. In April 2001, she lost her left eye in a blast from a rocket-propelled grenade while reporting on the Sri Lankan civil war. After that, she started wearing her signature black eye patch. She covered conflicts in Chechnya, East Timor, Kosovo, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe.

As a reporter for United Press International, she interviewed Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi in 1986, months after the United States bombed the country, and was lowered down into a smuggling tunnel in the Gaza Strip in 2005.

UPI was Colvin's first reporting job, which she landed a year after graduating from Yale in 1978 -- the Long Island native covered crime and general news in Trenton, N.J., for United Press International. She answered to the agency's New York Metro desk.

Joseph Gambardello was city editor on the desk and sometimes edited her articles. They worked together for about four years.

He remembers once taking her to lunch at the Yale Club in Manhattan -- a club restricted mostly to Yale alumni and professors.

"I would never have gotten into on my own," Gambardello told UPI. "The meal was mediocre.

"She was smart and I respected her as a woman and as a journalist. She was always good company and had a disarming smile."

He recalled that just about every man who worked for the New York metro desk "seemed to have a crush on her.

Gambardello, who now works for the Philadelphia Inquirer, said he knew Colvin wanted to eventually work as a foreign correspondent but had no sense she desired to work specifically in conflict zones.

Colvin became Paris bureau manager for UPI in 1984, around the same time the agency transferred Gambardello to the London bureau. Colvin made her first trip to Libya two years later, during the U.S. bombing of Tripoli in 1986.

"I was in Geneva at the time covering an [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] meeting and recall being concerned for her safety," Gambardello said. "I sometimes think that her being there during the bombing and surviving exposed a level of risk taking that lingered just below the surface and led to her career as a war correspondent."

Months after the bombing, Colvin scored one of the biggest interviews of her career with the eccentric Gadhafi, considered by some to be "the most dangerous man in the world." She was the first reporter to interview him after the bombing.

"Why didn't you tell me they were going to bomb my house?" she said he demanded of her during one of the multiple interviews she ultimately had with him.

Other former UPI reporters and editors said Colvin clearly itched for a foreign post, but John Phillips, former Bahrain bureau manager, said he never got the sense she had a "death wish, as some detractors have claimed after she was killed by Syrian shellfire."

They worked together in Kuwait covering the Iran-Iraq war in 1987. He wrote in an article after her death that she once warned him against drawing the attention of authorities as they searched for U.S.-made Hawk missiles that were meant to shoot down Iranian Silkworm missiles but had hit a U.S. oil tanker and an oil terminal instead.

"Stop looking at the troops through the binoculars," she told him. "You'll get us arrested."

Around the time of her interview with Gadhafi, Colvin left UPI for The Sunday Times, first as a Middle East correspondent and later as a foreign affairs correspondent.

A Private War, which stars Rosamund Pike as Colvin and Jamie Dornan as her colleague, photographer Paul Conroy, is based on a Vanity Fair article by Marie Brenner, focusing largely on Colvin's years with the Times and the emotional toll of witnessing so much violence. She sought treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder and alcoholism, and some questioned why her editors at the Times allowed her to go into dangerous situations.

"The Sunday Times has blood on its hands," Brenner said she overheard someone say at a celebration of life ceremony at London's Frontline Club.

Phillips, too, questioned her editor's lack of experience of working in the field amid a conflict.

Conroy was with Colvin on her last assignment, though the two had worked together multiple times before her death, including during the lead-up to the fall of Tripoli, Libya. The two concocted an elaborate plan in which they would sneak into the city ahead of other members of the press aboard Conroy's sailboat. They ultimately never made the voyage into the capital.

Conroy said Colvin had a healthy fear of danger, but she overcame that fear to get the story.

"Remarkably, where other war correspondents had gradually grown immune to the horrors of war, their senses dulled and emotions blunted over time by their harrowing experiences, Marie had succeeded in retaining her sense of outrage throughout her illustrious 25-year career," Conroy wrote in his book, Under the Wire.

"It was what drove her to cover conflicts when she was well into her 50s. And it was what made her one of the best at doing it, earning her comparisons to her journalistic heroine, the legendary Martha Gellhorn."

Colvin and Conroy snuck illegally into Syria to cover the civil war in February 2012. They reported from the Baba Amr district of the rebel-held city of Homs in eastern Syria, about a dozen miles northeast of Lebanon. They were in a makeshift media center when the shelling began.

Colvin and a French photographer, Remi Ochlik, died at the scene, while Conroy sustained a critical injury to his leg.

The Syrian government blamed the attack on Syrian rebels, but Conroy said they were targeted by Syrian government troops.

In July 2016, the Center for Justice & Accountability filed a lawsuit against the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad on behalf of Colvin's sister. Colvin's family said her location was traced from her satellite phone by Syrian intelligence to the media center.

"The transmissions were intercepted, and they were tracked to their GPS coordinates," said one of the legal team, Scott Gilmore. "On top of that, there was a whole web of informants who were already out searching for the journalists. Any journalist in Homs ... could have been a target."

Journalists across the globe mourned Colvin's death.

"I was devastated," Gambardello said. "We had not been in contact for years, but I always had fond feelings for her."

Rosamund Pike, Jamie Dornan attend 'A Private War' premiere

<< Show Caption >>