Ed Karrens: It was a story of the highest intrigue and complexity. It told of political espionage, burglary, big money payoffs and telephone bugging. Its cryptic jargon included words such as "gemstone" and "plumbers." It was a story the world came to know as the Watergate Affair.

In January, when seven men were found guilty of breaking in and bugging the Democratic National Headquarters, few people thought there was more to the story. But the presiding judge on the trial, U.S. District Chief John Sirica, thought differently. He suggested further investigation. A Senate Committee was formed, headed by Sam Ervin of North Carolina, and then a bombshell hit.

Convicted defendant James McCord wrote a letter to the Court. In it, he said he was under political pressure to plead guilty. He implicated high Government officials, including formal Attorney General John Mitchell.

President Nixon started his own investigation and his Press Secretary, Ron Ziegler, called all the previous White House statements on Watergate inoperative. Demands for an explanation from the President grew more insistent as winter turned to spring. The press, politicians and the people wanted answers.

Finally on April the 30th, President Nixon addressed the nation.

President Richard M. Nixon: "The easiest course would be for me to blame those to whom I delegated the responsibility to run the campaign. But that would be a cowardly thing to do. I will not place the blame on subordinates, on people whose zeal exceeded their judgment and who may have done wrong in a cause they deeply believe to be right. In any organization, the man at the top must bear the responsibility. That responsibility therefore belongs here in this office. I accept it."

Ed Karrens: But that wasn't all. In that same speech, an indication of how involved Watergate might be became apparent when Nixon announced these resignations.

President Richard M. Nixon: "In one of the most difficult decisions of my Presidency, I accepted the resignations of two of my closest associates in the White House, Bob Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, two of the finest public servants it has been my privilege to know. Because Attorney General Kleindienst, though a distinguished public servant, my personal friend for 20 years, with no personal involvement whatever in this matter has been a close personal and professional associate of some of those who are involved in this case, he and I both felt that it was also necessary to name a new Attorney General. The Counsel to the President, John Dean, has also resigned."

Ed Karrens: The CIA and Federal investigators reported that attempts were made to cover up the Watergate Affair by high-ranking members of the White House. So the stage was set. The nationally broadcast Senate Watergate hearings replaced soapbox operas as the daily affair for housewives viewers.

In his testimony, former Counsel to the President, John Dean, started with a prepared six-hour document in which he asserted the President joined in the Watergate cover-up plot.

John Dean: "It is my honest belief that while the President was involved that he did not realize or appreciate at any time the implications of his involvement, and I think that when the facts come out, I hope the President is forgiven."

Ed Karrens: John Mitchell, who headed the Nixon Campaign Committee until shortly after the Watergate burglary, was questioned by Senator Ervin.

Senator Sam Ervin: "Did you at any time tell the President anything you knew about the White House horrors?"

John Mitchell: "No, sir, I did not."

Senator Sam Ervin: "Did the President at any time ask you what you knew about Watergate?"

John Mitchell: "Not after that first discussion that we had on the telephone, I believe it was on June 20th."

Senator Sam Ervin: "Well, if the cat hadn't had any more curiosity than that, he'd still be enjoying his nine lives, all of 'em."

John Mitchell: "Well, I hope the President enjoys eight more."

Ed Karrens: But it was Alexander Butterfield, former White House Aide, whose testimony opened up a whole new aspect to the hearings. He was asked by Minority Counsel Fred Thompson.

Fred Thompson: "Mr. Butterfield, are you aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the President?"

Alexander Butterfield: "I was aware of listening devices, yes, sir."

Fred Thompson: "When were those devices placed in the Oval Office?"

Alexander Butterfield: "Approximately the summer of 1970; I cannot begin to recall the precise date. My guess, Mr. Thompson, is that the installation was made between -- and this is a very rough guess -- April or May of 1970 and perhaps the end of the summer or early fall 1970."

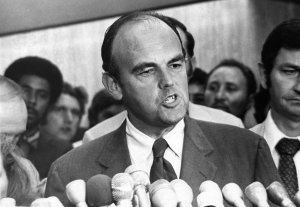

Ed Karrens: If there were tapes made of conversations which took place in the White House, the Senate Committee surmised those tapes could be used to clear up some of the contradictory testimony. So they requested the President deliver certain tapes to them, and so did Archibald Cox, the man picked by the President to be the special Watergate prosecutor.

Citing the separation of power and executive privilege, Nixon refused both requests. The Committee then subpoenaed the tapes, and so did Cox.

Archibald Cox: "This afternoon, I received from the White House a letter declining to furnish the eight requested tapes. Careful study before requesting the tapes convinced me that any blanket claim of privilege to withhold this evidence from the grand jury is without legal foundation. It therefore becomes my duty promptly to seek subpoenas and other available legal procedures for obtaining the evidence for the grand jury. The effort to obtain these tapes and other documentary evidence is the impartial pursuit of justice according to law."

Ed Karrens: The insistence of Nixon and the persistence of Cox led finally to a high-noon showdown on October the 20th. Cox was fired, Attorney General Elliot Richardson quit rather than fire Cox, and Richardson's deputy, William Ruckelshaus, was fired because he, too, wouldn't dismiss Cox. It was quite a day, and it caused an unusual ventilation of public outrage. A few days later, Nixon relented and said he would give up the tapes.

One week later, however, the Court was informed that two of the requested tapes, one of Nixon and Dean and the other of Nixon and Mitchell, did not exist.

But the saga of the tape did not stop there. Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, said she accidentally hit the record button while transcribing one of the tapes, and this error may have resulted in part of an 18-minute gap on one of the tapes, 18 minutes of buzz and hum. White House lawyer Fred Buzhardt was questioned by reporters about the tape.

Unknown Speaker: "When the President learn that this phone was on the tape, sir?"

Fred Buzhardt: "I don't know precisely."

Unknown Speaker: "Well, why didn't he, for instance, say so at his news conference the other day?"

Fred Buzhardt: "I don't think he understood that it was, at that time, that it was on a subpoenaed conversation."

Unknown Speaker: "There were no further bombshells to come, why didn't the President say"

Fred Buzhardt: "Well, I don't think this is a bombshell."

Unknown Speaker: "Is this something important to you, Mr. Buzhardt?"

Fred Buzhardt: "It seems very important. It'll probably will be I don't know how construed. We thought we ought to make a report to the Court after having reviewed these; we reviewed them all."

Ed Karrens: The Watergate investigation did not end in 1973. What it brings in 1974 can only be speculated. But its effect on many people in 1973 was summarized succinctly by a member of the President's own party, Senator Lowell Weicker of Connecticut.

Senator Lowell Weicker: "It's what all of us do from here that will give to Watergate its meaning. All of us almost allowed America to be taken away from us, and it's gonna take all of us to keep it."