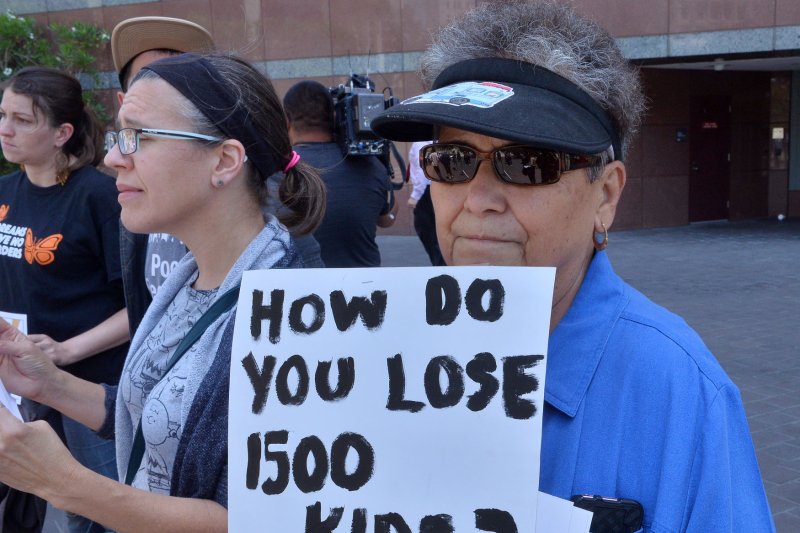

June 8 (UPI) -- The fates of 1,475 migrant children recently came into question when the Department of Health and Human Services reported them as "missing" in a report to Congress in April.

These children are not missing in the sense that they have disappeared. They simply remain unaccounted for in the follow-ups conducted by the U.S. government with the families into which the children were placed.

Since 2012, I have conducted research with undocumented youth and young adults and their families in Los Angeles.

Related

I have spoken with hundreds of undocumented youth who crossed the U.S. southern border without a parent or legal guardian between 2007 and 2016 -- often referred to as "unaccompanied minors." When apprehended at the border, they are processed by the Department of Health and Human Services and placed with a "sponsor" in the United States, typically a family member, who is responsible for their safety and well-being.

While my research may not explain why the government has failed to keep track of these individuals, it reveals the various challenges facing the 180,000 children who have been placed with sponsors in the United States since 2013.

My time with unaccompanied youth in churches, support groups, immigration courtrooms, summer and weekend camps, community cultural festivals and family gatherings reveals that children may end up leaving their sponsor's care for reasons ranging from financial need to their pursuit of their own idea of a better life. I use pseudonyms to respect confidentiality.

Feelings of responsibility

In my conversations with recently arrived migrant youth, they have expressed feeling like a financial burden to their sponsors. In many cases, their sponsor is someone from whom they have been separated for many years, such as a parent or older sibling, or someone they have met for the first time.

Many have told me how basic requests like needing a new toothbrush, deodorant, socks or calling cards to communicate with family abroad make them feel as if they're burdening the poor families with whom they are living. For example, I met a young Salvadoran man who was placed in his aunt's care, who reported feeling more comfortable asking his legal case manager about where to get food at local food banks rather than requesting more food from his aunt.

Along with feeling responsibility for themselves, many young people feel a sense of responsibility for others, primarily to their home communities and the families they left behind. That sense may trump the responsibilities and expectations of sponsoring families in the United States.

For example, Mario recalls arriving at his aunt and uncle's home in Los Angeles from El Salvador at the age of 16. Mario's aunt and uncle were financially and emotionally supportive but mandated that he attend high school full-time in exchange for their support.

This conflicted with Mario's motivation for migrating to the United States, which was to work and support his mother and two younger siblings back in El Salvador.

Mario's decision to work rather than attend school meant he would also leave his aunt and uncle's home.

He said, "Well, it wasn't that I had to leave school, but I wanted to. I was being supported when I was here [his aunt and uncle's house], but I felt bad 'cause of my brothers and my mom back over there. Nobody was helping them. I decided I wanted to work so I could get out of there. And that's what I did."

Unmet expectations

Some young people I spoke with said they felt disillusioned with life in the United State.. They may leave their sponsors' home when expectations don't match reality.

This was the case for Alejandra. She grew up with her grandparents in Guatemala until the age of 14, when her mother in Los Angeles sent for her.

Alejandra was told by her mother and grandmother she would be visiting her mother in Los Angeles for the summer of 2011, but was "just devastated because later they told me that all of it was just a lie." Alejandra's mother had actually arranged for her to permanently live in Los Angeles. Alejandra explained she felt deep distrust at realizing her mother's dishonesty and resentment about being separated from the grandmother who raised her.

Unable to come to terms with her mother's decision, Alejandra eventually ran away at age 17 and lived in a local youth shelter until she finished high school. When I interviewed her two years later, she had still not spoken to her mother.

Edgardo arrived in Los Angeles from El Salvador at the age of 11 in 2007. He was met in Los Angeles by his aunt, whom he described as very strict. Edgardo was disappointed by his aunt's requests to help out at home with things like babysitting his cousins so that she could work more hours as a housekeeper.

Edgardo left his aunt's home at 17 and began working in a furniture warehouse. He said: "I was trying to go back to school and so I never got to finish school, and I am still trying to work on that right now... I want to go to college."

Not having yet realized his goals, Edgardo also spoke during our interview about wanting to help his unaccompanied peers:

"There's a lot of people out there that are younger than me and still make it through, you know? But it's really hard and that's why I want to like help out other kids that are like had that same mentality that I had when I got here."

![]() "I don't really have anybody to guide me through my whole life except for like school book. School only taught me like so much you know... teach me like, life skills or like life lessons that would help me out."

"I don't really have anybody to guide me through my whole life except for like school book. School only taught me like so much you know... teach me like, life skills or like life lessons that would help me out."

Stephanie L. Canizales is an assistant professor of sociology at Texas A&M University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.