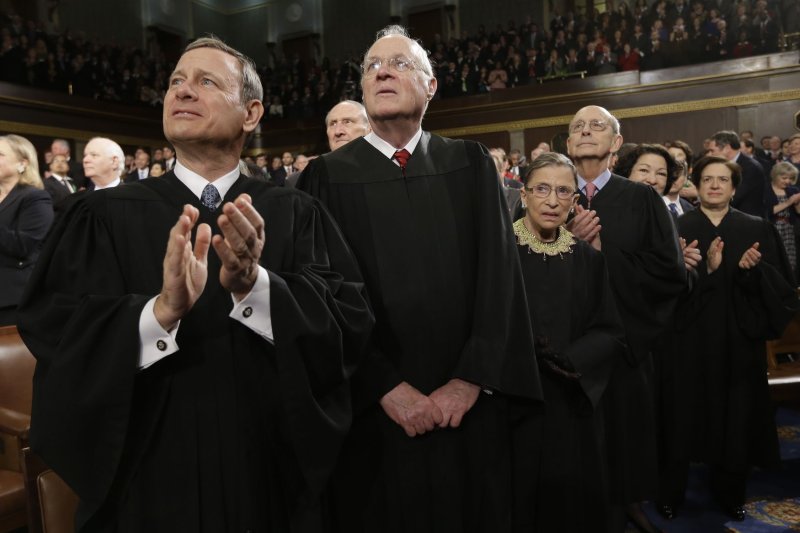

Supreme Court Justices, from left, Chief Justice John Roberts, Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan applaud before President Barack Obama's State of the Union address during a joint session of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC on February 12, 2103. UPI/Charles Dharapak/Pool |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, March 31 (UPI) -- While the Texas case on affirmative action in college admissions is still pending, the U.S. Supreme Court surprisingly agreed last week to hear an affirmative action case out of Michigan that promises to be a genuine mover and shaker.

Before hearing the two same-sex marriage cases last week -- challenges to California's Proposition 8, which limits marriage to heterosexual couples in the state, and to the Defense of Marriage Act, which limits federal benefits and considerations to heterosexual couples across the nation -- the justices said they would hear argument on whether Michigan or any state can ban race- or sex-based preference in government actions, particularly in university admissions.

The underlying law is much broader than the admissions issue.

In the November 2006 election, 58 percent of Michigan's voters approved a proposal that amended the state Constitution. The amendment banned discrimination, or the granting of preferential treatment, in public education, government contracting and public employment based on race, sex, ethnicity or national origin.

After the election, a group of plaintiffs led by the Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action filed suit challenging the constitutionality of the amendment.

Eventually the full 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 8-7 the law violated the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.

In asking for U.S. Supreme Court review, the state said: "Michigan recognizes that affirmative action has long been controversial; some state entities use it for some programs, some do not. But until now, no court has ever held that, apart from remedying specific past discrimination, a government must engage in affirmative action. This [Supreme] Court has said just the opposite, holding that all racial classification by government entities [is] presumptively invalid and subject to the strictest scrutiny."

Justice Elena Kagan, who was U.S. solicitor general before reaching the high court in August 2010, did not participate in accepting the case.

Argument in the case should be heard next term.

The justices already heard argument in October on the University of Texas admissions policy.

During that argument, Justice Anthony Kennedy led the skeptics from the bench.

More than three-fourths of freshmen enroll at the University of Texas through a state law that gives automatic admission to students in the top 10 percent of their high school classes. For the rest, the school considers a number of factors, including race.

Two white students denied UT admission under the policy challenged it in federal court. But a three-judge appellate panel upheld the admissions policy, and the full 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, one of the most conservative in the country, refused to rehear the case by a vote of 9-7.

The majority said UT's admissions program was "narrowly tailored," as required by the 2003 Supreme Court precedent in Grutter vs. Bollinger.

In argument before the Supreme Court, however, the admissions policy appeared to be in trouble with at least four conservative justices. Kennedy, a key swing vote, showed some doubt, and appeared in the end not to be convinced of its constitutionality, most observers reported.

The liberal bloc, expected to support the policy, was reduced from four to three because of the withdrawal of Kagan, again because she was U.S. solicitor general in the early phases of the case.

The courts have wrestled with the concept of affirmative action in college admissions for decades. Is diversity so compelling an interest that public colleges and universities can treat applicants differently because of the color of their skin?

The arithmetic of the modern court, conservatives versus liberals, doesn't bode well for the survival of affirmative action in college admissions even though the Obama administration filed a brief strongly supporting the University of Texas policy.

In 1978's Regents of the University of California vs. Bakke, a Supreme Court majority found the admissions policy of the UC Davis Medical School unconstitutional when it set aside spaces for minorities, but a plurality recognized that diversity was a legitimate goal.

In 2003, the high court went both ways, striking down the University of Michigan's undergraduate admissions policy but upholding the admissions policy of the Law School, though both used race as a determining factor.

In Gratz vs. Bollinger, the justices ruled 6-3 the university's undergraduate admissions guidelines were unconstitutional. The guidelines used a number of factors to evaluate an undergraduate applicant, assigning a numerical value to each factor.

Those scoring above 100 were considered eligible to fill the limited number of slots. However, minorities automatically received a 20-point bonus.

Two white students, who normally would have been admitted but weren't, challenged the policy in court.

The prevailing opinion written by the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist said, "Because the university's use of race in its current freshman admissions policy is not narrowly tailored to achieve [the school's] asserted interest in diversity, the policy violates the equal protection clause" of the 14th Amendment.

The other University of Michigan case, Grutter vs. Bollinger, was handed down the same day with Justice Sandra Day O'Connor joining four liberals to form the five-member majority for a different result.

In Grutter, the university's Law School chose applicants based on a number of factors, including race, but gave no numerical weight to race. Instead, the Law School tried to achieve a "critical mass" of students, black and Native American, who might otherwise not be included.

Again, the policy had been challenged by a white student who was qualified to be admitted to the Law School but wasn't.

O'Connor said in her majority opinion, "The law school's narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body is not prohibited by the equal protection clause" of the Constitution.

She said the law school's policy survived even strict scrutiny, the toughest of three levels of scrutiny used by the courts (the lower levels are "reasonable review" and "intermediate review").

But, she warned 10 years ago, racial preferences should not last forever, a warning cited in the Michigan case.

"It has been 25 years since Justice [Lewis] Powell first approved the use of race to further an interest in student body diversity in the context of public higher education" in 1978's Bakke, O'Connor said. "Since that time, the number of minority applicants with high grades and test scores has indeed increased. ... We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today."

In Grutter, Justice Kennedy joined the three conservatives, Rehnquist, Justice Antonin Scalia and Justice Clarence Thomas, in dissent, but also wrote separately.

In what may be an indication on how he will rule in the Texas and Michigan cases, Kennedy condemned "preferment by race."

"Preferment by race, when resorted to by the state, can be the most divisive of all policies," Kennedy wrote in 2003, "containing within it the potential to destroy confidence in the Constitution and in the idea of equality."