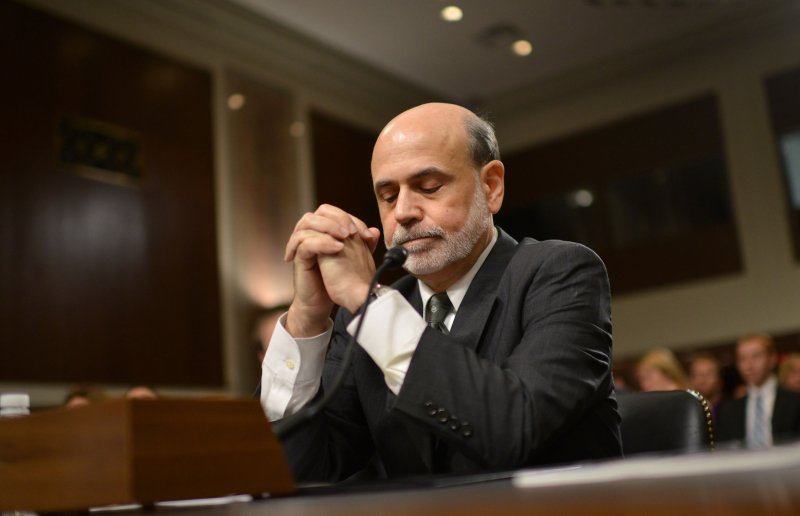

Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke testifies on the Board's Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to Congress during a Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee hearing on Capitol Hill on July 17, 2012 in Washington, D.C. UPI/Kevin Dietsch |

License Photo

COLLEGE PARK, Mass., July 18 (UPI) -- Much like a drug addict, the U.S. economy is hooked on the Federal Reserve's easy money policies.

Since the financial crisis, the Fed has pumped trillions of dollars into banks and financial markets -- first, by buying banks' troubled real estate loans and then by purchasing long-term Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to push down mortgage rates.

This rescued Wall Street banks from near-death experiences, while federal regulators shuttered more than 480 smaller banks. Unable to cope with more cumbersome regulation, many other regional banks sold out to bigger institutions.

Bank consolidation reduces competition for deposits and drives down certificate of deposit rates. Retired Americans who rely on interest from savings to help pay bills have taken an enormous loss. At resorts around the country, for example, many once prosperous seniors are tending bar and waiting on tables.

Yield hungry investors have scarfed up the junk bonds of troubled companies. Should the Fed permit interest rates to rise, defaults would burn investors in a replay of the financial crisis.

Homebuyers, farmers and speculators, armed with cheap mortgages, have bid up home and agricultural land values and should the Fed let mortgage rates rise, many wouldn't be able to sell properties as needed and ultimately would default on loans.

Smaller businesses can't get credit from disappearing regional banks. Smaller real estate developers are selling out to big national builders, which can access the bond market to finance projects. Reduced competition pushes up new home prices but, when cheap money goes away, those mega-builders will be unable to sell options-ladened homes and some will default on their bonds.

Like the first crack taken by the dysfunctional personality, easy money made the economy function somewhat better for a brief period. From the beginning of the recovery through September of last year, gross domestic product grew at a modest 2.2 percent.

But like the addict, it needs ever larger doses to stay on task. Last September, the Fed nearly doubled purchases of long-term securities but growth has since slowed to about 1 percent.

Early in June, Chairman Ben Bernanke caused panic by merely stating that as the economy improved the Fed would scale back securities purchases. Two weeks later, forced to backtrack, he stated easy money would continue as long as it takes -- that may be forever.

The White House and Congress have done little to fix what caused the Great Recession: a growing trade deficit with China that saps demand for U.S. goods and destroys jobs; dysfunctional federal policies that invest in bogus alternative energy schemes and limit drilling for oil offshore; burdensome business regulations that raise the cost of new projects; and bank reforms that enrich the Wall Street Banks, while starving America's biggest jobs creators -- small businesses -- of credit.

Easy money is the opiate of the U.S. economy. It has few prospects for genuine improvement as long as President Barack Obama pursues an extreme left-wing agenda, conservatives in the House of Representatives indulge in the fantasy that free markets can solve every malady of mankind right down to athletes' foot; and senators posture like toga-clad aristocrats attending the games on Mount Olympus.

With growth slowing, the Fed may have to pump even more cash into the economy with diminishing results. Sooner or later the recovery could falter and, much like Europe, a few pockets will prosper but much of the rest of the country, like Spain and Italy, will sink into double-digit unemployment.

--

(Peter Morici is a professor at the Smith School of Business, University of Maryland School, and former chief economist at the U.S. International Trade Commission. Follow him on Twitter: @pmorici1)

--

(United Press International's "Outside View" commentaries are written by outside contributors who specialize in a variety of important issues. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of United Press International. In the interests of creating an open forum, original submissions are invited.)