(Informatique)

DUBLIN (WOMENSENEWS)-- The sit-down interview took place over two nights, behind the walls of the convent where they both live.

On the first night, Sister B opened the gates and directed me to her apartment where Sister A was waiting. I didn't meet any other members of their religious order as I walked through the convent.

As I positioned my Dictaphone for my story for The God Slot, a program on Ireland's National Public Service Broadcaster, RTÉ Radio 1, the nuns looked at the recording equipment with suspicion. But they didn't back out.

It was Feb. 11, almost a week after the publication of the McAleese Report, a damning publication linking the Irish State with the incarceration of over 2,500 women between 1922 and 1996 and failing to supervise their care. In reality this number is likely to be much higher but many records did not survive.

I was there so that Irish nuns, for the first time, could comment on a long-simmering scandal over subject matter that has drawn high-profile attention, including the 2002 movie The Magdalene Sisters.

The interview was agreed to on the condition the nuns or their order was not identified because they feared the backlash that would follow if their names became public.

In return for anonymity, the nuns spoke frankly and openly about what they believed has become a "one-sided anti-Catholic forum" about the Magdalene Laundries in the Irish media. During our conversation, both stated that they had nothing personally or directly to do with the orders involved in the scandal. Nothing directly or personally, they emphasized.

They also made clear that they strongly believed the religious orders that operated the laundries had done nothing untoward and perhaps even should be commended.

'Apologize for What?'

"Apologize for what?" demanded Sister A, her voice choked with emotion. "Apologize for providing a service? We provided a free service for the country . . . All the orders involved saw a need in society and they tried to respond to it in the best way that they could and there was a terrible need for a lot of those women because they were on the street, with no social welfare and starving. We provided shelters for them. It was the 'no welfare state' [a term often used to describe the Ireland of that era] and we are looking with today eyes at a totally different era."

Sister B echoed that view. "They were not laundries as such. They were refuges originally. Washing was taking in to fund the running of them and to make a living."

The McAleese Report, recommended by the United Nations Committee Against Torture, confirms the Irish State gave lucrative cleaning contracts to 10 Magdalene Laundries, located across the country and run by four orders of nuns. The contracts included one to clean the uniforms of the Irish Defense Force.

"All the shame of the era is being dumped on the religious orders . . . the sins of society are being placed on us," said Sister B.

"I'm glad the report was written because it kind of takes the lid of an era of Irish society that anybody under 60 years of age hasn't a clue about," said Sister A, as she shifted in her seat. "I think it's great that the women are releasing themselves of the stigma to be able to speak and find their voice. To say I was in the Magdalene home; I survived; I'm here; I made it in life. OK with bad memories; but I made it and that is an achievement."

Magdalene Asylums Began in 1765

The Magdalene Laundries grew out of the Magdalene Asylums, the first of which was set up in 1765 as a short-term reformatory for "fallen" women. In 1829 the Catholic Church appropriated them and they began turning into the longer-term laundries, run by the Sisters of Charity, Sisters of Mercy, Sisters of Charity of Our Lady of Refuge and the Good Shepard Sisters.

The causes for women to be sent to the laundries expanded to include unmarried mothers, women with "special needs," and women considered as too pretty or tempting to men. Those without families anxious or willing to claim them could stay for a long time, some stayed their whole lives. The inquiry found six months was the average length of stay.

In addition to their work in the laundries, the women were required to endure long periods of prayer and silence for their sins.

"The nuns profited from our labor," said Maureen Sullivan, 61, the youngest known-survivor in an interview. "I often saw big orders coming in with new materials and rosary beads and sweaters for the nuns . . . I saw that they kept money rolled up in rubber bands and hidden in biscuit tins and they were then given up to the bishop."

The McAleese Report concluded that the institutions barely broke even and were not run on a commercial basis.

"We have always lived very frugal lives. The money paid for their food and their keep," said Sister B, referring to the women who worked in the laundries.

Asylum records estimate that 30,000 women were held captive in Ireland's Magdalene Laundries. The youngest was 9 and the oldest was 89. Almost 900 women and children died while living and working in them. Ireland's last such home closed in October 1996.

The oldest known Magdalene survivor, Madge O' Connell, died on May 16, aged 97.

The McAleese report said that 10 percent of Magdalene residents were sent in by their families, almost 9 percent were referred by the Roman Catholic Church and 17 percent entered voluntarily. There is no surviving documentation on the rest. No evidence of sexual abuse was included in the report.

Church Blamed for Stigmatizing Women

The Catholic Church's role was not explored by the McAleese report. However, a crucial argument by survivors, which has gotten wide press attention, is that the church encouraged families and the state to stigmatize "fallen" women and send them away.

Sister B strongly protested that view. "The society those women grew up in encouraged them to be compliant and to conform and all those who ended up in the laundries went against that stereotype," she said.

My second evening with the two nuns came on Feb. 19, hours after Prime Minister Enda Kenny offered an official state apology to the women who suffered and announced plans to set up a compensation fund. Survivors could claim up to $260,000 for unpaid work and for physical, psychological and emotional damage.

Both nuns said the figure was excessive since residents in the Magdalene Laundries "did get their keep."

Said Sister A: "I understand there was a lot of pressure on Kenny to apologize and of course we are all sorry for the society of that time. I think it is very important to remember that he didn't just apologize for the state but he also apologized for the society. Because even if a woman did escape and jump the walls she still wasn't free from the stigma because the stigma was in society. It was a whole society thing. It wasn't just because they were in the Magdalene."

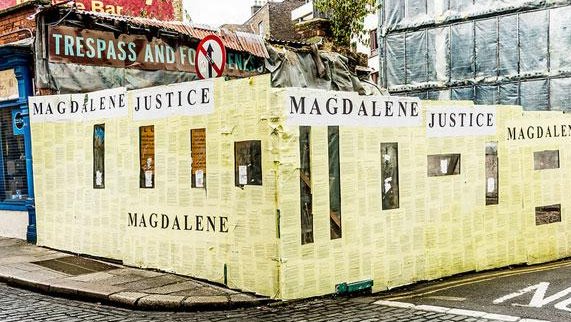

Justice for Magdalenes, a voluntary advocacy group, ended its campaign on May 22. "JFM has achieved its twin objectives of an official State apology and the establishment of a compensation scheme . . . Responsibility to ensure justice is delivered now rests with Irish society, including the Church, State, families and local communities," reads a statement on the voluntary group's website.

The Law Reform Commission of Ireland is currently assessing how the government could provide payment to former residents. These plans have also urged Magdalene survivors in Northern Ireland to seek similar justice from the British government, reported the Washington Post on May. 1.

I told the nuns that I recently interviewed survivor Maureen Sullivan. After her father died she was placed in New Ross Magdalene Laundry, Co. Wexford, aged 12, in the care of the Good Shepard Sisters.

"By day I would work in the laundry but by night I would sleep in St. Aidan's Industrial School," Sullivan said in a phone interview. "It was long, hard tedious work and because I was small they made a timber box for me to sleep in. I remember being hidden in a tunnel when the school inspectors came. I can only assume that this was due to the fact that I was too young to be working in the laundry."

She went on: "I didn't know why I was put in. I didn't know how long I would be there. I couldn't contact my family. I couldn't speak to anyone except to God when I was forced to pray for penance for sins I didn't commit. I still blame the nuns: the stigma they caused took over my life and forced me to pretend I was a different person with a different past."

I asked the Sisters what they thought of this story.

Sister B sat forward to answer. "I know a lot of abuse cases have been reported in the media and some of these may have been exceptional circumstances but I'm sure they were not everyday events. In terms of abuse, I'd say the residents did work very hard but the nuns would say they worked hard too. Everybody worked hard. Factory work is hard today. It's monotonous. It's tedious. The hours are long."

In a statement to the Irish press, the Magdalene Survivors Together said the group was "shocked, horrified and enormously upset" by how the nuns portrayed the laundries.

"I think they [the nuns] are stopping the women from healing. The women were starting to heal and forgive but now it's going to be very difficult for them," survivor Maureen Sullivan told The Journal, a Dublin based website.

But some who had heard the radio program stood up for what the nuns said in the interview. "I have wanted the nuns to speak out, because those of us who lived through that time know what life was like . . . Those girls were abandoned by their families . . . well done Sister A and Sister B," wrote Elizabeth Murphy in an email to The God Slot.