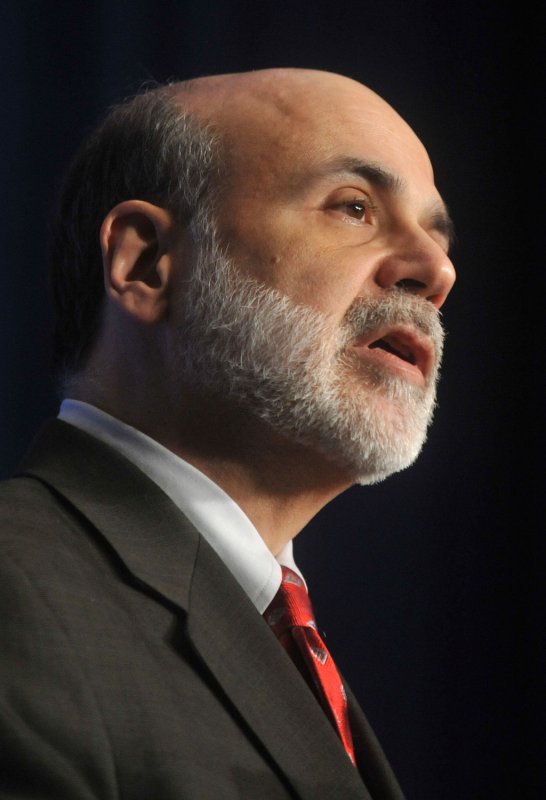

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke. UPI/Kevin Dietsch |

License Photo

WASHINGTON, Feb. 28 (UPI) -- Ben Bernanke, America's central banker, may have saved the Atlantic alliance with an incautious remark to Congress last week.

It went against etiquette and convention for a chairman of the Federal Reserve Board to reveal that an inquiry was under way into the operations with Greece of Goldman Sachs and other U.S. finance houses.

There are two issues here. The first was Goldman's acknowledged work with the Greek government earlier in this decade to securitize certain income streams (like tourist admission fees to Greek antiquities) and some complex currency swaps. The effect was reduce the Greek national debt by some $2 billion in 2002, which helped get Greek debt levels below the threshold required for admission to the euro.

The second issue is more perilous. It relates to European suspicions that Goldman (and other U.S. financiers and hedge funds) might be shorting Greek bonds through the credit default swaps market. In plain English, they might be placing a big bet on a further fall of the euro and a Greek default on its sovereign debt.

This is not far off a declaration of financial war. It may be capitalism but it is a most unfriendly act to play the markets in order to profit on the humiliation of a NATO ally. And given the current low esteem in which Goldman and other finance houses are currently held, it could if proven rebound badly on them -- however rational a financial decision it may have been to make such a bet.

American banks and American financiers are even less popular in Europe these days than they are in Main Street, USA. They are blamed for the sub-prime mortgage crisis, for selling lots of toxic mortgage-backed securities to gullible European banks, for inventing lots of bizarre new securities and derivatives that were supposed to spread debt and thus to make it safer. And they are blamed for being the poster boys of ruthless Anglo-Saxon capitalism.

All of this makes conventional financial strategies like shorting a stock or a currency a much more delicate matter than usual. The NATO alliance is not what it was. President Barack Obama declined to attend the EU summit. The fall of the Dutch government means that their troops will be leaving Afghanistan and, along with the British, they were among the few doing much fighting. The hopes that the arrival of Obama would magically restore the Atlantic alliance to its old warmth and vigor have proved to be hollow.

So there was an important diplomatic aspect to Bernanke's statement that "Using these instruments (default swaps) in a way that intentionally destabilizes a company or a country is counterproductive."

It was a way to mollify the Europeans and to send a clear warning to the hedge-funders and short-sellers in Wall Street that this game was getting dangerous and was now about something rather deeper and broader than just finance. (A pity Bernanke was not sending the same signal when the sub-prime and derivatives bubbles were inflating out of control back in 2007 but that's another matter.)

On the other hand, Wall Street financiers who are shorting the euro might simply be hedging bets they have made last year when it looked as if the euro would rise and the dollar fall. Moreover, those same Wall Street financiers have a fiduciary duty to do the best they can for their investors.

Finance is a tricky and complex matter, particularly when politics and diplomacy become involved. And so it is interesting to turn to Walter Bagehot, the 19th-century English economist and philosopher (and founder of The Economist), who noted, "The business of banking ought to be simple; if it is hard, it is wrong."

Bagehot was an extraordinary figure, a polymath who wrote on physics and philosophy and literature and produced in "Lombard Street" (1873) the first classic book on banking. His advice on the role of central banks in financial panics and crises has never been bettered: "to avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely, to solvent firms, against good collateral, and at high rates."

Kevin Mellyn, an American economist and consultant (whose last book on financial regulation won the Larosiere Prize from the Institute of International Finance), has produced a sharp and cogent new analysis of the current financial crisis. His book -- "Financial Market Meltdown" -- is both a paean of praise to Bagehot and a sharp assault on the asset securitization experts of Wall Street whose model, he says, "provided the explosives to blow up the global economy."

He proposes that cheap money and more credit will not bring the financial system back to normal (as if the "normal" of 2007 is a happy or sustainable state that we wish to resume). Instead, he suggests that "credit has morphed from the lifeblood of the economy into a pathogenic drug … It has ceased to support healthy functions, real commerce and wealth creation, by being channeled into things that destroy social and economic tissue."

That is the essence of the European charge sheet against "Anglo-Saxon capitalism." The irony is that Mellyn is an American. But he is not alone in questioning Bernanke's efforts to restart the U.S. economy by flooding the system with more cheap credit, secured on dubious collateral. The alternative is brutal; to support only solvent firms and make them pay higher interest rates, on strong collateral, in order to wring the swollen levels of debt out of the system.

It is an alternative that Bernanke may yet have to face, since he and the other central bankers are starting to run out of financial ammunition. They cannot long continue creating liquidity and pumping ever more deficit spending into the economy. Investors will go on strike.

So two cheers for Ben Bernanke, diplomat, whose revelation that Goldman Sachs is under investigation reassured the Europeans that American officials do care about their Atlantic allies and do not want to see their currency deliberately undermined.

But a third cheer must await Bernanke's navigation of the endgame of his massive bet on the ability of the U.S. economy to recover from the banking crisis. Having soothed the ruffled feathers of the Europeans, Bernanke must now inspire the animal spirits of Americans and restore confidence at a troubled time. If he can do that, and show himself as smart a psychologist as he has been a diplomat, he'll deserve to wear Bagehot's polymath mantle.