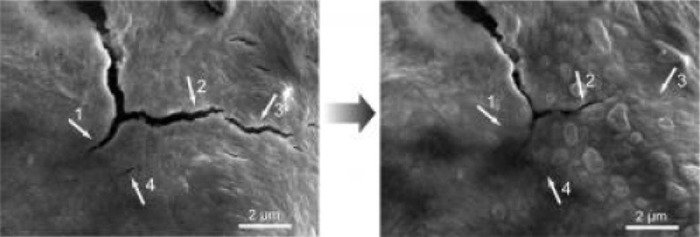

Left: An electron micrograph shows cracks left in a self-healing polymer coating due to swelling of its silicon electrode during charging. Right: Five hours later, the smaller cracks have healed. Credit: C. Wang et al, Nature Chemistry

PALO ALTO, Calif., Nov. 18 (UPI) -- A self-healing battery electrode could bring a new generation of lithium ion batteries for electric cars, cell phones and other devices, U.S. researchers say.

A team from Stanford University and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory report they've developed a stretchy polymer that coats the electrode, binds it together and spontaneously heals tiny cracks that develop during battery operation.

"Self-healing is very important for the survival and long lifetimes of animals and plants," Stanford post-doctoral researcher Chao Wang said. "We want to incorporate this feature into lithium ion batteries so they will have a long lifetime as well."

The self-healing polymer contains tiny nanoparticles of carbon so it can conduct electricity, the researchers reported in the journal Nature Chemistry.. When it breaks or cracks, the broken ends are chemically drawn to each other and quickly link up again, mimicking the process that allows biological molecules such as DNA to assemble, rearrange and break down.

"We found that silicon electrodes lasted 10 times longer when coated with the self-healing polymer, which repaired any cracks within just a few hours," said Stanford Professor Zhenan Bao, whose research group has been working on flexible electronic skin for use in robots, sensors, prosthetic limbs and other applications.

The coated electrodes worked for about 100 charge-discharge cycles without significantly losing their energy storage capacity, the researchers said.

"That's still quite a way from the goal of about 500 cycles for cell phones and 3,000 cycles for an electric vehicle," scientist Yi Cui, who led the research with Bao, said, "but the promise is there, and from all our data it looks like it's working."