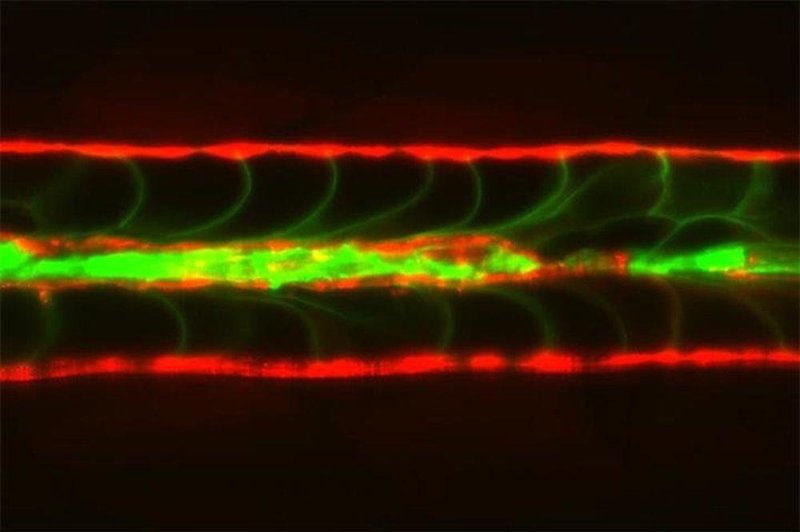

Bioluminescent markers revealed newly fluid-filled sheath cells, in red, replacing collapsed inner cells, in green, inside the zebrafish's notochord. Photo by Jennifer Bagwell/Duke University

June 22 (UPI) -- The cells that make up the developing backbone of zebrafish can self-repair, new research shows. Unfortunately these cells disappear as the backbone matures.

Before developing a backbone, embryonic and newly hatched zebrafish are supported by a notochord -- a proto-spine. The soft spine structure is similar to a water-filled garden hose. A shell of epithelial cells protects fluid-filled cells called vacuolated cells.

Previous studies suggest tiny sacs in the membranes of vacuolated cells, called caveolae, prevent the fluid cells from popping as the young fish begin swimming.

Researchers engineered zebrafish to be without caveolae, to see whether the tiny sacs are essential to spinal chord health and development.

"In the caveolar mutants, you see these serial lesions up and down the notochord, and yet the mature spine formed normally," Michel Bagnat, an assistant professor of cell biology at Duke University School of Medicine, said in a news release. "That was very puzzling to us."

Researchers conducted follow up experiments, using bioflourescent proteins to mark the two types of cells in the notochord. Images showed the vacuolated cells occasionally burst like a water balloon. When they do, an epithelial sheath cell fills the void and morphs into a vacuolated cell.

Additional tests showed nucleotides released by the popped fluid cell trigger the repair mechanism in the epithelial sheath cells.

"These cells, which reside in the discs of both zebrafish and man, seem capable of controlling their own repair and regeneration," said Bagnat. "Perhaps it is a continuous release of nucleotides that is important for keeping the disc in good shape."

Previous studies suggest epithelial cells decline in number as organisms age, which may explains why degenerative disc disease is more common among the elderly.

Researchers published their findings in the journal Current Biology.