New research suggests a thick, salty ocean may be hiding beneath Pluto's heart-shaped depression. Photo by NASA/UPI |

License Photo

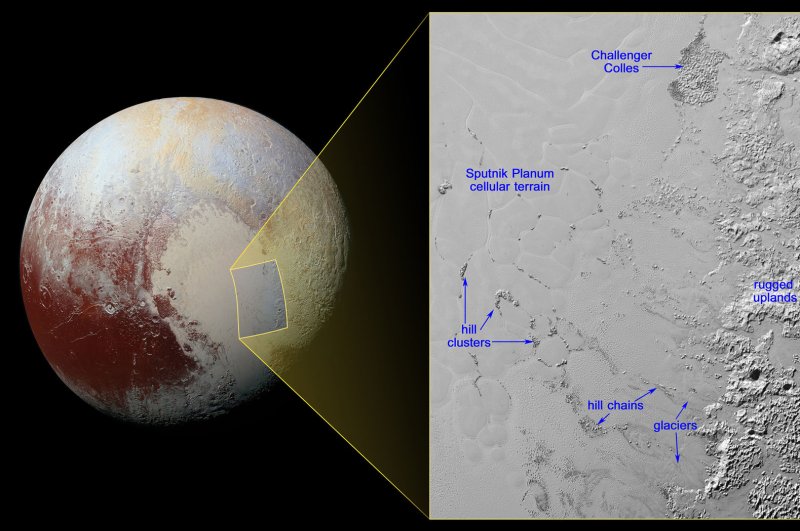

PROVIDENCE, R.I., Sept. 23 (UPI) -- One of the most remarkable features revealed by last year's Pluto flyby is the large, relatively bright and smooth heart-shaped region known as Tombaugh Regio, or simply "The Heart."

New research suggests it's more than just appealing to the eye and easy to spot; it also may be hiding a massive buried ocean.

A mounting body of evidence suggests a liquid ocean sits beneath Pluto's icy shell. The latest analysis suggests that ocean is situated beneath Pluto's heart.

The clue to the location of the ocean lies in the tidal axis linking Pluto and its largest moon, Charon. The dwarf planet and moon are tidally locked, meaning the same sides of each orb always face each other -- Charon orbiting at the same pace that Pluto spins.

Because tidal forces should exert greater forces of areas of greater mass, scientists would expect the region at the center of the tidal axis to feature greater mass. The region at the center of Pluto's tidal axis is Sputnik Planum, a large crater forming the western lobe of Tombaugh Regio.

Logically, it would make sense for a crater or depression to feature less mass, not more.

"An impact crater is basically a hole in the ground," Brown University geologist Brandon Johnson said in a news release. "You're taking a bunch of material and blasting it out, so you expect it to have negative mass anomaly, but that's not what we see with Sputnik Planum. That got people thinking about how you could get this positive mass anomaly."

Researchers believe there's a layer of nitrogen ice beneath Sputnik Planum, but not one thick enough to make the region a positive mass anomaly.

When an impact crater is formed, some of the depressed surface naturally rebounds back upwards, pulling the contents beneath it along for the ride. Geologists call the process isostatic compensation. Models suggest an isostatic compensation event involving an underlying liquid layer, with the right density, could have imparted to Sputnik Planum a positive mass anomaly.

In simulations, the scenario that best explains a positive mass anomaly beneath Sputnik Planum is a 62-mile-thick ocean with a salinity of 30 percent.

"What this tells us is that if Sputnik Planum is indeed a positive mass anomaly -- and it appears as though it is -- this ocean layer of at least 100 kilometers has to be there," Johnson explained. "It's pretty amazing to me that you have this body so far out in the solar system that still may have liquid water."

The new research was published this week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.