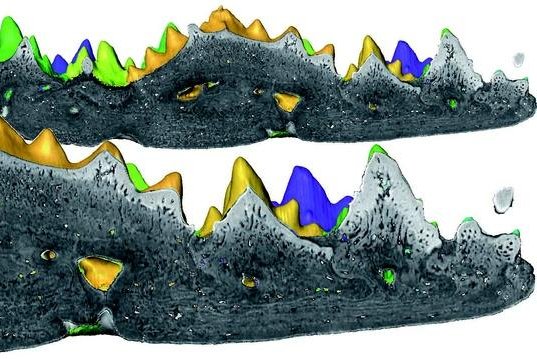

Models of the tooth fragment helped illustrate its potential evolutionary path. Photo by Naturalis/Martin

LEIDEN, Netherlands, June 24 (UPI) -- Many scientists have suggested all teeth, regardless of species, originated from scales. Now, there's solid evidence.

Paleontologist Martin Rucklin, a researcher at the Netherland's Naturalis Biodiversity Center, found the evidence in the collections of the natural history museum in Stockholm, Sweden -- a 410 million-year-old fragment of a primitive fish fossil.

With the help of Phil Donoghue of the University of Bristol, Martin was able to examine the internal structure of the fragment using blasts of high-energy X-rays. The imaging technology revealed the fragment to be an early tooth plate.

Researchers say it's the earliest example of teeth, and were also able to show the tissue likeness between scale and tooth. The new research also shows that teeth were present in the absence of jaw bones, suggesting the two features evolved separately.

Using their internal images -- including shots taken from every conceivable angle -- Martin and Donoghue built computer models to visualize how how the teeth might have evolved.

"With powerful computing, we combined thousands of X-rays and produced computer models reconstructing the growth of the first teeth," Martin said in a press release.

Researchers say a better understanding of how teeth evolved can help them trace the evolution of other vital organs and anatomical features.

"We will have to look into more basal-jawed vertebrates and also jawless fossils," Martin explained. "We will come ever closer to the origins of the complex system of our teeth. This has been an important innovation during the evolution. Nowadays, more than 98 percent of the vertebrates have jaws. We use them intensively every day."

The new research was published this week in the journal Biology Letters.