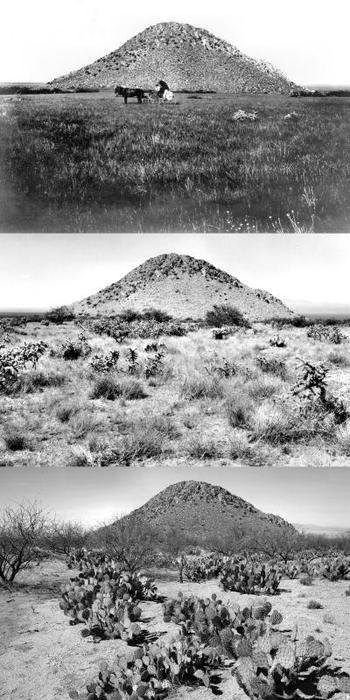

Repeat photography is one of the tools range ecologists use to document how lands change: In 1902 (top), open grassland is surrounded by scattered desert hackberry plants at the foot of Huérfano Butte, south of Tucson, Ariz. By 1941, burro weed and cholla cactus popping up, along with velvet mesquite trees. In 2007 (bottom), the grass cover had given way to velvet mesquite trees, and prickly pear have replaced cholla as the dominant cacti. Credit: Mitchel McClaran/University of Arizona

TUCSON, Jan. 23 (UPI) -- Plants can adapt to drought but there are limits, and arid grasslands in the U.S. Southwest are already are approaching these limits, researchers say.

Water demands of many plant communities can fluctuate in response to water availability, giving them a capacity for resilience when changing climate patterns produce periodic droughts, but that resilience can weaken if droughts are prolonged, they said.

"From grasslands to forests, plants can tolerate low precipitation, but if drought conditions continue past a certain point, this resilience will fail," U.S. Department of Agriculture researcher Susan Moran said.

Once that limit is reached, water-starved plants lose their ability to take advantage of increased precipitation even if the drought ends and is replaced by wetter conditions, said Moran, who is also a professor of soil, water and environmental science a the University of Arizona.

Researchers saw evidence of that limit in some of the study areas in Utah, Arizona and New Mexico, she said.

"Prolonged, warm drought makes a difference," Moran said in a university release. "To date, it appears there is resilience, but in the more sensitive biomes like grasslands, we are starting to see evidence of decreasing resilience. And as more and more ecosystems increase in aridity, more will reach this threshold."