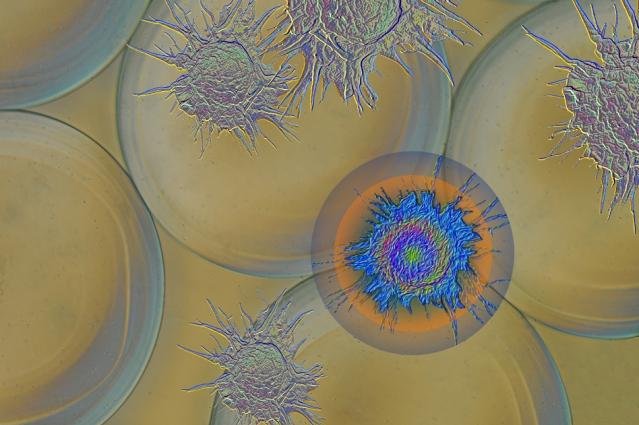

The image shows a white blood cell called a macrophage, colored blue, which has been blocked from initiating the formation of scar tissue. Photo by Felice Frankel/MIT

March 20 (UPI) -- Scientists have found a way to prevent scar tissue from forming around medical implant devices.

Fibrosis is the formation of extra fibrous connective tissue in an organ. It is a reactionary response most commonly deployed for reparative purposes, although fibrosis can also occur in response to a foreign object.

When scar tissue builds up around a medical implant, the device can struggle to function or stop working completely.

Scientists at MIT identified an immune system signaling molecule important to the biomechanics of fibrosis.

"This gives us a better understanding of the biology behind fibrosis and potentially a way to modulate that response to prevent the formation of scar tissue around implants," Daniel Anderson, an associate professor in MIT's Department of Chemical Engineering, told MIT News.

To understand the fibrosis process, Anderson and his colleagues isolated various components of the immune system in mice. They found white blood cells called macrophages were essential to scar tissue formation.

Macrophages attach to a cell surface receptor called CSF1. When scientists blocked the receptor, scar tissue stopped surrounding implants. The lab tests showed macrophages were still able to carry out other important immune system functions.

"We show that you preserve many other important immune functions, including wound healing and phagocytosis, but you lose this fibrotic cascade," said Josh Doloff, a postdoctoral research at MIT's Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. "We're preventing the macrophages from toggling into an activated warning state where they sound the alarm for this massive immune response to show up."

Researchers conducted their initial tests using implants made of alginate, a material derived from algae. They repeated their experiments using ceramic implants and implants made of a plastic called polystyrene.

"It's generalizable to many different types of biomaterials, and hopefully will also be generalizable to many platforms for different purposes," Doloff said.

Currently, physicians reduce implant fibrosis by prescribing drugs that suppress the entire immune system. Scientists hope the latest findings -- detailed in the journal Nature Materials -- will inspire safer and more effective alternatives.

"If you use a broad-spectrum drug, you may be getting rid of cell types that are important for reducing fibrosis or even for other vital immune functions in the body -- wound healing or fighting off parasites, bacteria or viral infections," Doloff added.