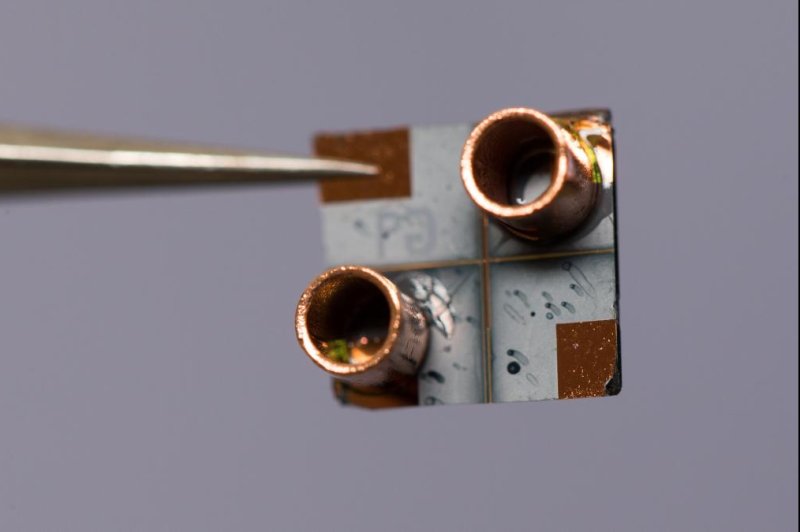

A tiny diagnostic microchip could help doctors identify drug-resistant blood infections more quickly. Photo by BYU

PROVO, Utah, Oct. 8 (UPI) -- When trying to identify and treat drug-resistant blood infections, doctors don't have a lot of time, but current diagnostic tests often take as long as three days to deliver a result. It's a time lag that sometimes proves fatal.

That's why a team of researchers at Brigham Young University are so encouraged by their latest invention -- a speedier blood test for antibiotics-resistant bacteria. The team's work is part of a nationwide collaborative effort sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

"The goal is to take a blood sample and know, within an hour's time, what the bacteria is and what antibiotic resistance profile it has," Adam Woolley, a chemistry professor at BYU, said in a press release. "Then you can hit it with whatever is going to work and presumably save a lot of lives."

Rare drug-resistant blood infections require rare types of antibiotics -- drugs doctors can't afford to waste. Faster diagnostic tests can help save patients' lives, and also save doctors from wasting limited supplies of antimicrobial drugs.

The key to researchers' new diagnostic technology is integration. Their device is an attempt to design an all-in-one diagnostic system.

"What we're trying to do is put it all together," lead researcher Aaron Hawkins said. "To go from blood to diagnosis in a single system. This is a full-blown solution, not just aspects of the process. We put together a team to do something that hasn't been done before."

It's powered by an opto-fluidic microchip. The device will first filter out a sample's blood cells to isolate bacteria. DNA from the bacteria will be extracted, sequenced and scanned for matches with known sequences of drug-resistant strains. Potentially harmful bacteria DNA will get flagged with fluorescing molecules.

The microchip will sense the fluoresced light as the blood is pushed through a small channel. Researchers plan to install the the chip on a small, relatively inexpensive disposable cartridge.

Right now, the device -- detailed in the journal PNAS -- is still in the design and building phase. The process of perfecting and testing the technology could take another couple of years.

"We've got all the expertise needed to take on this project," Woolley added. "At BYU, faculty actually like to work with their colleagues across college lines -- and they do."