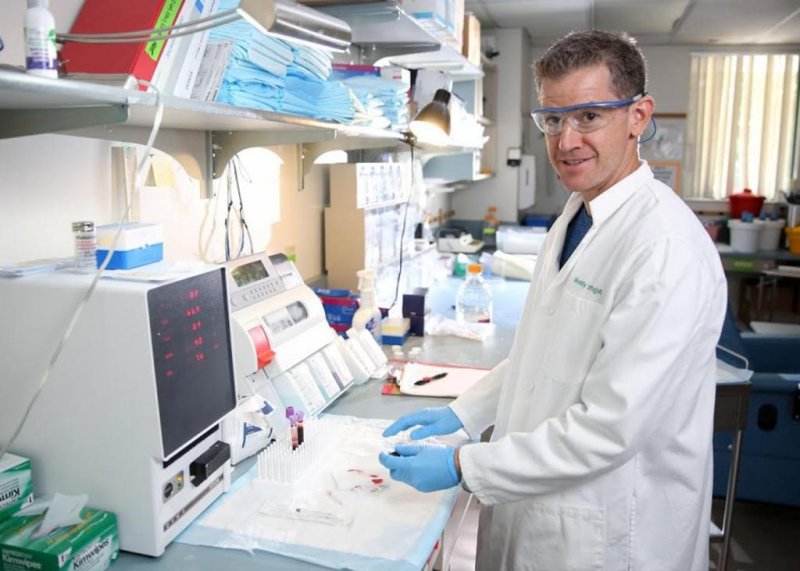

Andrew Lovering of the Department of Human Physiology at the University of Oregon has linked a common heart flap that doesn't close normally in infancy to serious health complications in individuals going into high altitudes. Photo: Charlie Litchfield/University of Oregon

EUGENE, Ore., June 30 (UPI) -- A small opening between the chambers of the heart, which usually closes during infancy but is thought to have only minor health effects in adults who have it, may cause problems at high altitudes, a new study found.

The study, published in the Journal of Applied Physiology, is one of many to come out of AltitudeOmics, an international project researching how the human body deals with low-oxygen environments.

The opening in the heart, called the foramen ovale, allows the developing heart of a fetus to pump blood until birth when the infant's lungs become functional and blood flow forces it to close. In about 40 percent of humans, it does not close all the way, becoming a patent foramen ovale, or PFO.

"This seemingly insignificant heart condition had significant impacts on human physiology at high altitude, including reduced breathing response, a reduced ability to oxygenate the blood and increased susceptibility to acute mountain sickness," said Andrew Lovering, a professor of human physiology at the University of Oregon, of the study, published in the Journal of Applied Physiology.

For AltitudeOmics, researchers brought 21 subjects to Bolivia in 2012, where various tests were performed at sea level, after arriving a research facility 17,257 feet high on Mount Chacaltaya, and then again after 16 days at that altitude. The purpose of the project is to determine how the body deals with low-oxygen scenarios, with PFO being one condition that can affect the amount of oxygen making it into the blood.

The subjects were split into groups with and without PFO and studied at rest and during exercise. Researchers measured gas exchange efficiency in the lungs and how subjects adapted to the altitude, finding little difference between PFO and non-PFO subjects at sea level and first arrival at altitude.

There was far less acclimatization among the PFO subjects after 16 days on the mountain. While on the mountain, 40 percent of PFO subjects still had acute mountain sickness while just 10 percent of non-PFO subjects had it.

A separate study, already accepted for publication in the Journal of Physiology, shows that subjects with PFO, during exercises at sea level, had a warmer resting temperature and difficulty cooling down when given cool air to breathe.

Robert Roach, director of the Altitude Research Center at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, said the purpose of the AltitudeOmics is to expand understanding of low-oxygen diseases, which can affect the heart and lungs, as well as some cancers, and develop treatments for those conditions.

The research also is partially funded by the Department of Defense.