Natural Resources Defense Council

CHICAGO, Oct. 6 (UPI) -- Hold on before dumping that gallon milk down the sink; just because it's past the "sell-by" date doesn't necessarily mean it needs to be thrown out.

More than 90 percent of U.S. consumers may be wasting money and prematurely throwing away perfectly good food because they misinterpret food labels as indicators of food safety, a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council and Harvard Law School's Food Law and Policy Clinic said.

The report called for changes in the way food manufacturers label their products.

"Expiration dates are in need of some serious myth-busting because they're leading us to waste money and throw out perfectly good food, along with all of the resources that went into growing it," said Dana Gunders, staff scientist with the NRDC's food and agriculture program. "Phrases like 'sell by', 'use by', and 'best before' are poorly regulated, misinterpreted and leading to a false confidence in food safety. It is time for a well-intended but wildly ineffective food date labeling system to get a makeover."

The study, "The Dating Game: How Confusing Food Date Labels Lead to Food Waste in America," is a follow-up to a 2012 NRDC report that found as much as 40 percent of the U.S. food supply ends up in the garbage each year.

The report found 91 percent of consumers occasionally throw food away based on the "sell by" date out of a mistaken concern for food safety even though none of the date labels actually indicates food is unsafe to eat.

An estimated 160 billion pounds of food is trashed in the United States every year, making food waste the single largest contributor of solid waste in the nation's landfills.

"Sell by" dates are used by grocery stores to determine when their stock should be rotated, they do not indicate the food is bad on that date. "Best before" and "use by" dates are intended for consumers, but they usually just estimate peak quality, again not an accurate date of spoiling or an indication that food is unsafe.

While the NRDC hasn't gotten any official feedback from food manufacturers, Gunders said preliminary conversations suggest the industry is interested in taking on the issue of food labeling, but they want it to be voluntary and not subject to federal regulation.

"I'm willing to let them try," she told UPI. "The question in my mind is: Can they really come to an agreement?"

Gunders said phrases that are used on food labels "need to have some meaning attached to them."

She said phrases such as "at their peak quality" or date of "maximum freshness" versus "use by" would make it easier for consumers to make appropriate decisions about shelf life.

"I think the important thing to note is those dates on food are not intended to indicate safety," she said. "We should not be using those dates."

Gunders said the upside of the loosely regulated system currently in place in the United States is that businesses can act now to clarify their labeling practices rather than wait for the Food and Drug Administration.

U.S. Rep. Nita Lowey, however, is calling for federal legislation. The New York Democrat said she plans to reintroduce the Freshness Disclosure Act that she has been trying to get through Congress since 1999.

"Under the current patchwork of state and federal laws, consumers are left in the lurch, forced to decipher the differences between 'sell-by' and 'best if used by,' and too often food is either thrown out prematurely, or families wind up consuming dangerous or spoiled food. The status quo is really quite absurd," she said in a statement.

David Fikes, vice president of consumer affairs for the Food Marketing Institute, said the food industry agrees there is some consumer confusion over labeling, although "we are not quite as convinced that the system is broken."

"They did us a lot of favors in terms of calling attention to this," he said of the Harvard/NRDC report. "But a lot of it, too, is just educating the consumer to the intent (of the labels)."

"Our industry has been at work on this issue for years," he said.

So, if the "sell-by" date on milk is meaningless from a safety standpoint, how do consumers figure out when they need to throw it out? Well, it will most likely start to smell and taste bad long before it will actually make you sick, Gunders said.

Food safety expert Ted Labuza, professor of food science and engineering at the University of Minnesota, says food manufacturers can't tell you the exact date the milk will start to go bad .

"The big problem with food is that the rate at which it goes bad -- the rate of decay -- is the function of the temperature the refrigerator is at," he said. "If you leave milk sitting out on the counter for 1 1/2 to 2 hours, you've lost a day of shelf life."

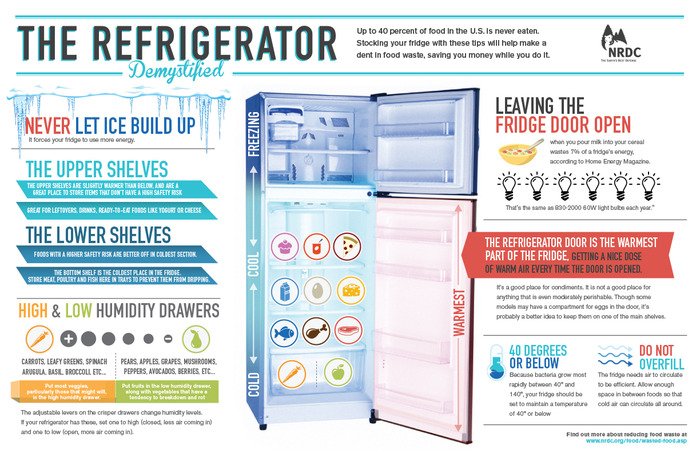

Keeping the refrigerator at 36 degrees Fahrenheit will help keep milk fresh. "A lot of people don't keep their refrigerators cold enough," he said. "That's the key."

And once the milk is open, don't put it back into the refrigerator without the cap. "Every time you open the gable top or bottle you are exposing the milk to microbes in the air that can then grow and spoil the milk," Labuza said.